-

Where did the Israelites go and how did they get there?

-

Where was the Red Sea crossing, Mount Sinai, Kadesh, and Mount Hor?

-

Where were the years of wilderness “wandering” spent?

Glen A. Fritz, c 2018

The biblical story of the deliverance of the Hebrews from Egypt, the Exodus, constitutes one of the great dramas of the ancient world. According to the Bible, a famine about 3700 years ago caused the Hebrew patriarch Jacob and his sons to settle in Egypt. Jacob’s progeny prospered and multiplied but were eventually enslaved by the Egyptians, who feared their growing numbers.

After 215 years in Egypt, a Hebrew named Moses was divinely appointed to lead his people out of Egypt. However, a stubborn Pharaoh stood in the way of their release, granting their freedom only after a series of ten divine plagues nearly destroyed the kingdom.

The size of the multitude was astounding: about 600,000 men, excluding women and children, that left Egypt (Exod. 12:37). A similar figure was given in the first census: 603,550 men 20-years and upwards, excluding the Levites, who were not tallied (Num. 2:32-33). Later, Moses referred to 600,000 footmen to feed (Num. 11:21). The final census in the 40th year tallied 601,730 “sons of Israel” 20 years-old and up (Num. 26:2, 51), and 23,000 Levite males older than one month (Num. 26:62).

The ultimate destination of the Hebrews was Canaan (Figure 1), a land that had been divinely promised to Jacob and his forefathers, Abraham and Isaac. Nevertheless, upon leaving Egypt, Moses’ first destination was the “mountain of God,” Mount Sinai, which he had visited at the close of his 40-year exile in Midian (Figure 1). It was there, at the “burning bush,” that he had been given divine instructions to return to the mountain with the Hebrew multitude after they were freed from Egypt (Exod. 3:12).

Figure 1 Map of the Exodus region showing locations mentioned in the text. The Exodus began in Goshen and ended at Jericho 40 years later.

1–The Journey to the Sea–

The Hebrews departed Egypt from Rameses, in Goshen, in the northeast Nile Delta. They hurriedly left after their initial observance of Passover on the 14th day of the first month of the Hebrew lunar calendar (Num. 33:3). This date falls in our March/April time frame.

The first two encampments listed beyond Egypt were Succoth and Etham. At Etham, God instructed Moses to detour from their path to Mount Sinai and to camp on the shore of a sea called Yam Suph. In the meantime, Pharaoh, regretting the loss of his slaves, had marshaled his army to pursue, and eventually trapped the Hebrews between this sea and the wilderness. Even as the Hebrews were bewailing their certain demise, the sea was miraculously opened, and the multitude passed safely to the opposite shore overnight. In the morning, the Egyptians followed and were destroyed when the sea closed in upon them.

The journey to the sea took an estimated 18-20 days (Fritz 2016a). The projected route is thoroughly explored in The Lost Sea of the Exodus (ibid.) A map of that routed can be viewed HERE

This sea, called Yam Suph in the Hebrew Scriptures, is identified as the Gulf of Aqaba on the east side of the Sinai Peninsula (ibid.) (see Figure 1). An analysis of the beachhead sizes, their accessibility, and the adjacent seafloor topography suggests that Nuweiba was the only feasible crossing site (Figure 1). However, water depths in the 9.7 mi. (15.6 km) path between Nuweiba and the Arabian coast approach 850 meters, which demands a great miracle, as the Bible repeatedly describes in Exodus 15 and verses like Psalm 106:9:

He [the Lord] rebuked the Red sea [Yam Suph] also, and it was dried up: so he led them through the depths, as through the wilderness.

2–From the Sea to the Mountain–

After the sea crossing, three days were spent in the wilderness of Etham (Num. 33:8), also called the wilderness of Shur (Exod. 15:22). The idea that the term Etham applied to both sides of the sea has often beleaguered pundits. This issue is fully addressed in The Lost Sea of the Exodus (Fritz 2016a, 220). In short, Etham generally refers to the coastal zone or the land sloping to the sea. However, the “wilderness of Etham” is more specific, referring to the difficult terrain that lies inland from the coastal zone.

Shur, meaning “wall,” was the functional definition of the barrier to east-west travel imposed by Mount Seir and the mountains of Edom and Moab (Figure 1). The “wilderness of Shur” was the southern extension Shur located east of the Gulf of Aqaba. On the far side of the theorized sea crossing site at Yam Suph, the wilderness of Shur coincided with the wilderness of Etham. The traditions that place the sea crossing near Egypt force the wilderness of Shur to lie adjacent to Egypt, which dislodges Shur from its logical biblical location at Mount Seir. (See The Lost Sea of the Exodus (Fritz 2016a, Appendix 7) for the complete arguments.)

The Hebrews then came to Marah (Hebrew: bitter) (Exod. 15:23; Num. 33:8-9), where miraculous intervention was needed to make the water drinkable. They encamped next at Elim (Hebrew: trees, e.g., palm grove), described as having 12 wells and 70 palm trees (Exod. 15:27).

The camp listed after Elim was on the shore of the sea, Yam Suph (Num. 33:10). Various Exodus theories and maps omit this inconvenient detail, which invalidates them.

One month after leaving Egypt, the Hebrews entered the wilderness of Sin (Exod. 16:1, Num. 33:11), somewhere in or near Midian (Figure 1). The miraculous provision of manna began at that time. The next encampments were Dophkah, Alush (Num. 33:12-12), and Rephidim (Exod. 17:1, Num. 33:14). There was no water in Rephidim, and water was miraculously provided at the rock in Horeb (Exod. 17:6). The battle with the Amalekites then ensued (Exod. 17:8-13).

The wilderness of Sinai was entered after two months’ travel from Egypt (cf. Num. 33:3; Exod. 19:1). The Hebrews departed the mountain on the 20th day of the second month in the second year of the Exodus (Num. 10:11), which calculates to a stay of eleven months and five days. During this time they received the Law (Torah) and built the tabernacle and its furnishings.

The low point of this stay was the idolatrous worship of a golden calf, which occurred under Aaron’s leadership while Moses was on the mountain receiving the tablets of stone (Num. 32:1-25). As a consequence, the Levites sought out the offenders and executed about 3,000 men (Num. 32:28).

3–The Identity of Mount Sinai–

Placing the Exodus sea crossing at the Gulf of Aqaba negates the tradition of a Mount Sinai in the Sinai Peninsula and logically shifts the mountain into northwest Arabia (Figure 1). This area hosted the land of Midian at the time of the Exodus, which was the place of Moses’ 40-year exile from Egypt.

A Midian location in Arabia was affirmed by Josephus, the 1st-century-AD Jewish historian (cf. Ant. II.xi.1, II.xi.2), Eusebius, the 4th-century AD Church historian (Eusebius et al. 2003, 70), and other historical sources. In his circa-AD-150 work, Geographia, the revered secular geographer Claudius Ptolemy placed towns associated with Midian in the region of Arabia Felix east of the Gulf of Aqaba (Stevenson 1932, 128-9, 137).

The Bible implies that Midian was in some proximity to the mountain of God (Mount Sinai), which Moses encountered while shepherding the herds of Jethro, the priest of Midian (Exod. 3:1 ff). This association is also inferred in Moses’ return from the mountain of God to Jethro in Midian (Exod. 4:18-19), and Jethro’s excursion to Mount Sinai with Moses’ wife and sons (Exod. 18:4). The Bible does not state that the mountain was in Midian.

Eusebius was more specific, defining Horeb as “the mountain of God in the land of Madiam. It lies beside Mount Sinai beyond Arabia in the Desert” (Eusebius et al. 2003, 95). For clarification, this “Arabia” of Eusebius was the Roman Province of Arabia that separated Palestine from the Arabia Felix that hosted Midian.

In recent decades, the Jabal al-Lawz mountain range, which lies east of the classical Midian location (Figure 1), has been touted as a likely location for Mount Sinai. This range has the tallest peak in the region, which fits the descriptions of both Philo (ca. 20 BC- AD 40) and Josephus. Philo (in Moses II.xiv.70) described the mountain of God as “the loftiest and most sacred mountain in that district…a mountain which was very difficult of access and very hard to ascend.” Josephus wrote that:

The mountain called Sinai…[was] the highest of all the mountains thereabout, and the best for pasturage, the herbage being good there; and it had not been fed on upon, because of the opinion men had that God dwelt there, the shepherds not daring to ascend up to it… (1960, Ant. II.xii.1).

He later reiterated: “…mount Sinai…is the highest of all the mountains that are in that country” (Ant. III.v.1).

The travel routes, geography, geology, and archaeology pertaining to the Jabal al-Lawz region are thoroughly examined in Fire on the Mountain (Fritz 2016b)

4–The Journey to Kadesh–

And when we departed from Horeb, we went through all that great and terrible wilderness…and we came to Kadeshbarnea (Deut. 1:19).

Kadesh (occurs 18 times) and Kadeshbarnea (occurs 10 times) appear to be used interchangeably in the Bible. Although Kadesh is commonly interpreted as “holy'” (Strong 1990, H6946), a better geographical meaning would be “set apart” (ibid. H6942). Barnea does not seem to be a Hebrew word, but it occurs in Arabic meaning “clay vessel.” Taken together, we get the picture of an area segregated from travel routes and habitation, topographically enclosed by the surrounding terrain, namely, a large canyon.

There were two visits to Kadesh in the Exodus, in the second year and in the fortieth year of the event. Hence, a conundrum arises in the near-encyclopedic itinerary of Num. 33 in that Kadesh is only named once (in Num. 33:36), with that entry pertaining to the 40th-year visit. Since the first visit to Kadesh was very consequential and was otherwise well-documented elsewhere (Num. 13-14 and Deut. 1:19-46), this absence seems unusual. To truly make sense of the Num. 33 itinerary, this problem needs to be addressed.

The Hebrews’ first arrival in Kadesh (Num. 13:26) occurred at the time of the first ripe grapes (Num. 13:20), referring to early summer (i.e., June). Because the multitude left Mount Sinai in April/May, their estimated travel time to Kadesh was two months or less. Kadesh, located on the southern border of Canaan (Figure 1), was divinely intended to be the staging point for the Hebrew conquest of Canaan (Num. 13:2).

The encampments between Mount Sinai and Kadesh include: Kibrothhattaavah, Hazeroth, Rithmah, Rimmonparez, Libnah, Rissah, Kehelathah, mount Shapher, Haradah, Makheloth, Tahath, Tarah, Mithcah, Hashmonah, Moseroth, Benejaakan, Horhagidgad, Jotbathah, Ebronah and Eziongaber (Num. 33:16-36). Although these names are cryptic-sounding, their meanings actually describe the landscape or an event. Moses noted that these stopping places were all divinely ordained:

…The LORD your God…went in the way before you to search out a place for you to pitch your tents, to show you the way you should go, in the fire by night and in the cloud by day (Deut. 1:32-33).

One important caveat about this itinerary is that “Moses wrote their goings out according to their journeys by the commandment of the LORD…” (Num. 33:2), not according to his own recollection.

Moseroth (Num. 33:30) was underlined in the above list because it appears to be a “codeword” for the first visit to Kadesh. Moseroth is the plural of Mosera or Moserah (Deut. 10:6), which was a “codeword” for mount Hor, the place of Aaron’s death at in the 40th year of the Exodus (Num. 20:22-27). Mount Hor was adjacent to Kadesh: “…the children of Israel, even the whole congregation, journeyed from Kadesh, and came unto mount Hor” (Num. 20:22). The geographical proximity between Kadesh and mount Hor is inferred by this set of verses:

- Kadesh is at the edge of Edom (Num. 20:16)

- The wilderness of Zin is Kadesh (Num. 20:1)

- The wilderness of Zin has a border along Edom (Num. 34:3)

- Mount Hor is by the border of Edom (Num. 20:2; 33:37)

Explaining further, Moseroth, meaning “chastenings” (Strong 1990, H4147-4148), was a reference to the divine death sentences meted out to the rebellious generation at Kadesh (Num. 14:22-23, 29, 32-34). Mosera meaning “chastening” (ibid.), referred to Aaron’s death. He and Moses were both chastened in Kadesh in the 40th year of the Exodus (Num. 20:12):

Because you trespassed against Me among the children of Israel at the waters of Meribah Kadesh, in the Wilderness of Zin, because you did not hallow Me in the midst of the children of Israel (Deut. 32:51 NKJV).

Similar “codeword” examples appear elsewhere in the Bible. “Water of Meribah,” meaning “water of strife” (Gesenius 1979, 4809), referred to Kadesh (Num. 20:13, 24; 27:24; Deut. 32:51). Likewise, the rock in Horeb was called Massa Meribah (Exod. 17:7) and Massa (Deut. 6:16, 9:22), with Massa meaning “temptation” (Gesenius 1979, 4532).

In summary, Moseroth (Num. 33:30-31) signified the first visit to Kadesh and the Hebrews’ great disobedience there. Moseroth is the plural of Mosera, which signified Mount Hor, where Aaron’s death was a reminder of his disobedience at Kadesh. Most importantly, knowing that Moseroth in Num. 33 was the first visit to Kadesh supplies an important clue in the itinerary that facilitates further analysis.

5–The Location of Kadesh–

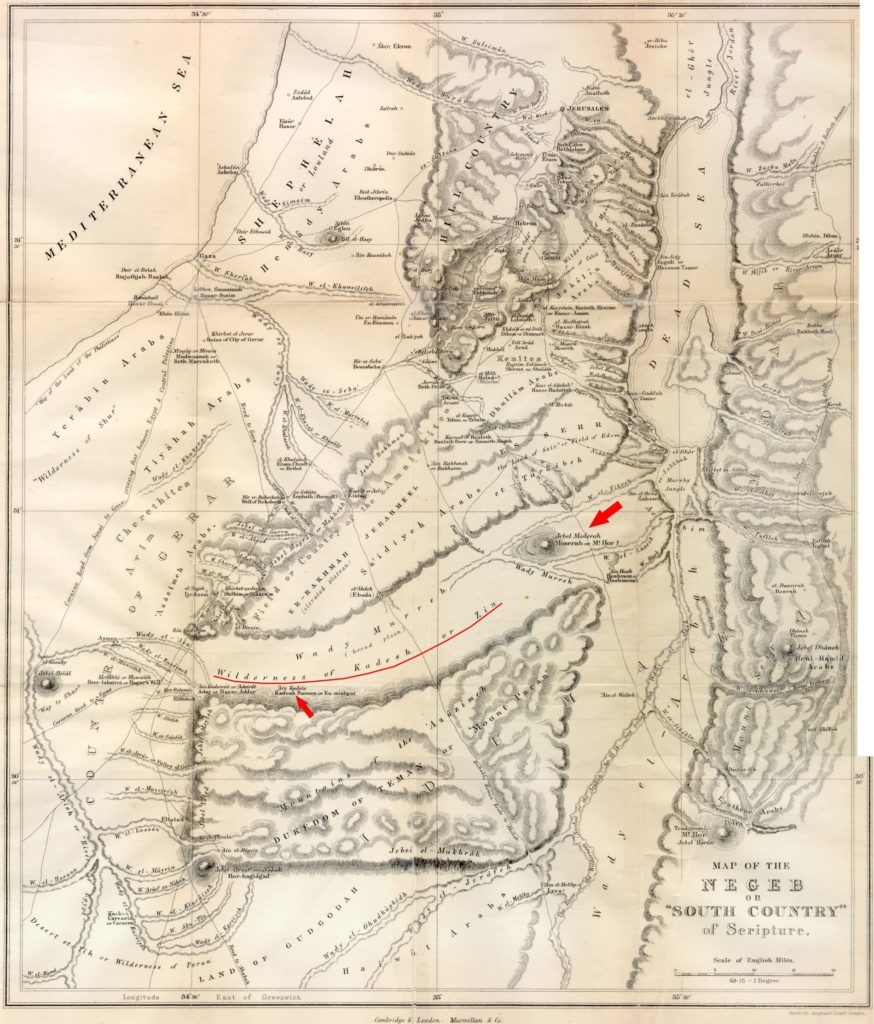

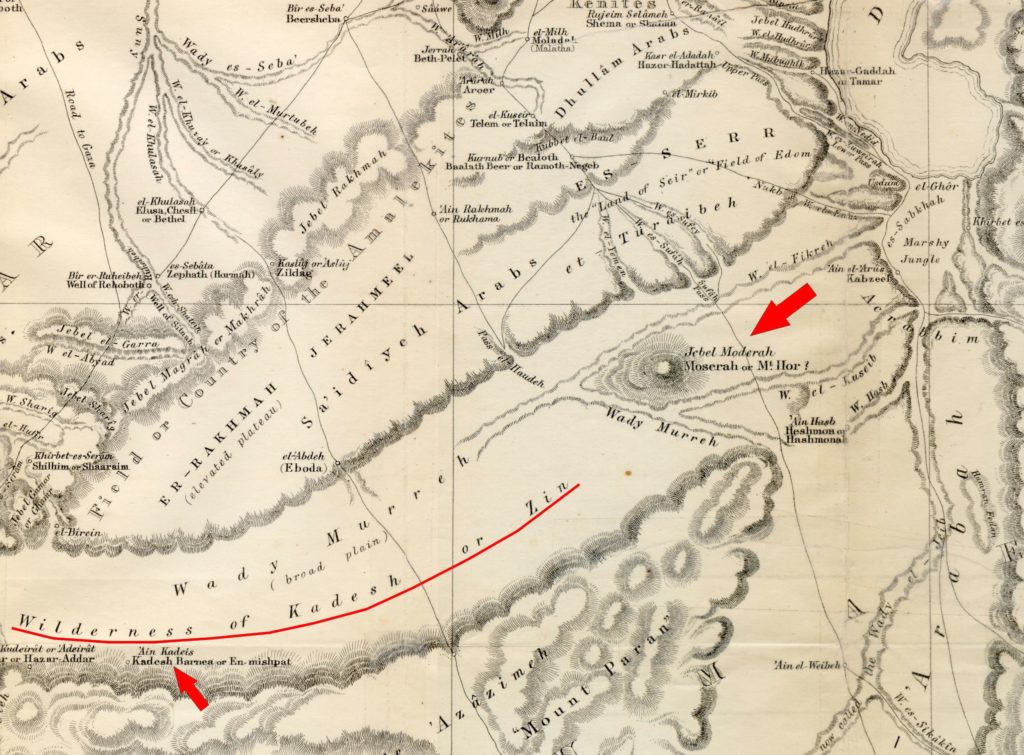

Linguistically, Moserah (mount Hor) resembles Jebel Madurah (Moderah), the Arabic name of an unusual, isolated mountain identified as mount Hor by some 19th-century travelers. (shown in the map in Figures 2a and 2b and the photos in Figures 3a and 3b.) Explorer Edward Wilton (1863, 128) observed that “…there is an evident affinity between Moserah and Moderah, the sibilants having a tendency to interchange with D.”

Figure 2a Kadesh and Mount Hor (Jebel Moderah) in Edward Wilton’s circa-1863 map of the “Negeb.” Although the geography and topography are crudely represented, Jebel Moderah is positioned accurately relative to the Dead Sea (click to enlarge).

Figure 2b Closeup of the Wilderness of Kadesh or Zin and Mount Hor (Jebel Moserah) on Wilton’s 1863 map (click to enlarge).

In Hebrew, Madurah can mean “pyre” (Gesenius 1979, 4071), perhaps referring to the use of signal fires on the mountain. Or, Madurah could be a distortion of the Hebrew madregah, meaning “a steep mountain, which one has to ascend by steps, as though it were a ladder” (Gesenius 1979, 4095). This description fits Jebel Madurah pictured in Figures 3a and 3b.

Biblical scholar Alfred Edersheim (1876, 190) aptly noted that: “…it is impossible to arrange the chronological succession of events as given in the Bible, except on the supposition that Moderah was Mount Hor.” Here is his 19th-century description of that area:

A day’s journey eastward from Kadesh, through the wide and broad Wady Murreh, suddenly arises a remarkable mountain, quite isolated and prominent, which Canon Williams describes a ‘singularly formed,’ and the late Professor Robinson likens to ‘a lofty citadel.’ Its present name Moderah preserves the ancient Biblical Moserah, which, from a comparison of Numb. 20: 22-29 with Deut. 10:6, we know to have been another designation for Mount Hor. In fact, ‘Mount Hor’ or Hor-ha-Hor (‘mountain, the mountain’) just means ‘the remarkable mountain’ (1876, 189).

This locale is depicted in the antique map in Figure 2b.

However, a longstanding tradition, suggested by Josephus (Ant. 4.4.7), placed mount Hor at Petra, which has subsequently been memorialized as Jebel Neby Harun (Arabic: “mount of the prophet Aaron”). But Petra’s historical position within ancient Edom clashes with the idea that it could host mount Hor during the Exodus because the Hebrews were forbidden to enter Edom (Num. 20:17-21; Deut. 2:4-5; Judges 11:17). In this regard, Auchincloss (1906, 9) noted that “the traditional site of the tomb of Aaron on Mt. Hor in Petra in the land of Edom is no more reliable than the traditional site of Adam’s tomb in the city of Jerusalem.”

I place Kadesh southwest of Jebel Madurah in the Biqat (valley of) Zin, the upstream watershed of Wadi Murreh and then Wadi Fikreh, which empties into the southwestern end of the Dead Sea. Fikreh is “Arabic for ‘vertebrae,’ referring to the chain of hillocks in its midst” (Bailey 1984, 47). Biqat Zin, also called Nahal Zin, is a 40 sq. mi. (150 sq. km) canyon that opens to the east, about 30 mi (50 km) southwest of the Dead Sea (see maps in Figures 1 and 2b and photo in Figure 4). Its southwestern rim hosts a number of springs, the largest currently being Ein Avdat (see Ain-Avdat 2018; Nahal Zin 2018 for more background).

Figure 4 Looking east over the canyon of Biqat Zin or Nahal Zin, presumed here to have been the site of Kadesh.

This Kadesh location differs significantly from the traditional site at ‘Ain Gadis, which lies 35 mi. (57 km) further to the southwest. Bible atlases and commentators have generally seized upon ‘Ain Gadis as a matter of tradition, ignoring the flimsy historical and geographical evidence. The site was originally selected in the 19th century because it sounds like Kadesh.

Kadesh was equivalent with the wilderness of Zin: “…the wilderness of Zin, which is Kadesh” (Num. 33:36). They were used interchangeably in the descriptions of the southern boundary of the Promised Land in Num. 34:3-5 and Josh. 15:1-4. Zin and Kadesh were both located in the wilderness of Paran (Num. 13:26), shown in Figure 1. Paran was spoken of as the general destination beyond Mount Sinai: “…the children of Israel took their journeys out of the wilderness of Sinai; and the cloud rested in the wilderness of Paran” (Num. 10:12).

The district of Kadesh/Zin began where the southern edge of the biblical Negev ended (Figure 1), which coincided with the southern bound of Canaan and the Promised Land (Num. 34:4). In fact, this southern boundary was termed the “border of the Negev” in the Hebrew text of Josh. 15:4. In the map in Figure 2a, this southern boundary would leave from the southwest Dead Sea and follow the ridge overlooking the Wilderness of Zin.

Unfortunately, the deficient traditional translations of Num. 34:3-5 and Josh. 15:1-4 have generated confusion about the position of this border relative to Kadesh, and the identity of Kadesh. This situation stems from the misinterpretation of the Hebrew word Negev as meaning “south” nine times in these passages. Negev actually means “parched” (Strong 1990, H5045).

As a point of information, Negev (or Negeb) never appears in the KJV, whereas a newer translation such as the NIV uses Negev 39 times. However, in the critical boundary passages of Num. 34:3-5 and Josh. 15:1-4, the NIV persists in inappropriately rendering Negev as “south.”

In the geography of Hebrew Patriarchs, the biblical Negev was a location, not a direction. It applied to the steppe region surrounding Beersheba in the southern part of the Promised Land that was given to the tribes of Judah and Simeon. When considering Palestine as a whole, it would be acceptable to use Negev to indicate the southern tier. However, within the territory of Judah, equating Negev with “south” is unacceptable because the Negev also extends into the eastern and western reaches of the tribal territory. This biblical Negev is not to be confused with the triangle-shaped political borders of the Negev desert that extends south to Aqaba.

6–The First Kadesh Visit–

Upon arriving in Kadesh, the Hebrews sent twelve spies into Canaan, one from each tribe. Ten returned with a faithless report that cast doubt on their ability to conquer the Canaanites (Num. 13:1-33). Joshua and Caleb were the two exceptions. The multitude chose to believe the bad report and defied their divine directive: “…the LORD sent you from Kadeshbarnea, saying, go up and possess the land which I have given you; then ye rebelled” (Deut. 9:23). As a consequence, those above age 20 were forbidden to enter the Promised Land and were sentenced to die off in the wilderness over the next 38 years (Num. 14:22-38).

After this moral failing, Moses told the people to leave Kadesh. But they rebelled again and marched north into Canaan to fight the Amalekites/Amorites (Num. 14:44/Deut. 1:44). After they were overwhelmed and scattered, Moses noted: “So you remained at Kadesh many days, the days that you remained there” (Deut. 1:46 RSV).

Sometime within this period, another rebellion against Moses was instigated by Korah, Dathan, and Abiram (Num. 16:1 ff). In the divine judgement that followed, “…the earth opened her mouth, and swallowed them up, and their houses, and all the men that appertained unto Korah, and all their goods” (Num. 16:32). A plague followed, causing 14,700 to die, besides those that died with Korah (Num. 16:49).

7–Banishment in the Wilderness–

Moses recorded little about next 37 years, which was a morose, shameful period in which the adult generation awaited their preordained, premature demise. It was an historical hiatus which awaited the rise of the next generation and the Hebrews’ second chance to enter Canaan.

The relative biblical silence about this time frame has led to various unfounded speculations, such as the idea that the Hebrews traveled all over the Arabian Peninsula. The supposed evidence is Hebrew-sounding place names (e.g., Moller 2008) and/or thousands of prehistoric stone structures throughout Saudi Arabia that originated from the Exodus (e.g., Rahimi 2018).

The traditional emphasis on “wandering” may contribute to the idea of widespread travel in this part of the Exodus. But, there are only three verses mentioning “wander” relative to the Exodus:

And your children shall wander [ra’ah] in the wilderness forty years, and bear your whoredoms, until your carcasses be wasted in the wilderness (Num. 14:33).

And the LORD’S anger was kindled against Israel, and he made them wander [nu’ah] in the wilderness forty years, until all the generation, that had done evil in the sight of the LORD, was consumed (Num. 32:13).

They wandered [ta’ah] in the wilderness in a solitary way; they found no city to dwell in (Psalm 107:4)

The Hebrew word most commonly translated as “wander” is shaga, meaning “to go astray” (Strong 1990, H7686). But, it is not used in the above texts.

A closer look at these verses suggests that “wander” may not even be the best translation. In Num. 14:33, the underlying ra’ah is more accurately rendered as “to pasture, tend, graze, feed” (Gesenius 1979, 7462), which implies sedentary behavior, not adventurism. In the second verse, nu’ah connotes being a “fugitive.” It can also mean “stagger” (Gesenius 1979, 5128), perhaps reflecting despair and weariness, not audacious wayfaring. The ta’ah in Psalm 107:4 is often translated as “erred” (Strong 1990, H8582).

Despite the “wander” connotations, the biblical evidence indicates that the multitude stayed in the confines of Kadesh and the neighboring Aravah valley during the 37 “silent years,” likely moving only to seek fresh pastures. Their most distant halting place was Eziongaber (Ezion Geber) at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba (Yam Suph) (Figure 1).

The Aravah or Arabah, meaning “plain,” extends for 103 mi. (166 km) between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba (Yam Suph). It is limited on the east by Mount Seir and on the west by the wilderness of Paran (Figure 1), which is poetically referenced as mount Paran (Deut. 33:2; Hab. 3:3). It is the logical place to seek pasture and water because it is the drainage basin between Seir and Paran. Its plain or “floor” has an average width of about 5 mi. (8 km). The Aravah has its own watershed divide 48 mi. (77 km) north of the gulf, at an elevation of 750’ (230 m). The northern half drains into the Dead Sea, the southern half drains into the gulf.

After the initial rebellion at Kadesh, Moses told the people to leave: “to turn [and] travel toward the wilderness of the way of Yam Suph (Deut. 1:40, my paraphrase). This wilderness refers to the Aravah, which hosted the north-south route between the Dead Sea and the gulf. A similar command appeared in Num. 14:25.

However, after their defeat by the Amorites, the Hebrews did not leave, but “remained at Kadesh many days…,” (Deut. 1:46, my emphasis). Hence, the initial period of their banishment was spent in Kadesh. Weeks, months, years? —we don’t know. Ultimately, they did move into the Aravah, also staying there for an extended time:

Then we turned and journeyed into the wilderness in the direction of the Red Sea [Yam Suph], as the LORD told me; and for many days we went about Mount Se’ir (Deut. 2:1 RSV, my emphasis).

We can infer that they traveled within the Aravah because there are four verses indicating that they left Kadesh and/or mount Hor via the “way of Yam Suph” (Num. 14:25, 21:4; Deut. 1:40, 2:1), which leads to the head of the gulf. Moses also explained that they went “through the way of the plain [Aravah]” to reach Elath and Eziongaber (Deut. 2:8). As already noted, the Aravah was the obvious place to seek water and pasture in this region.

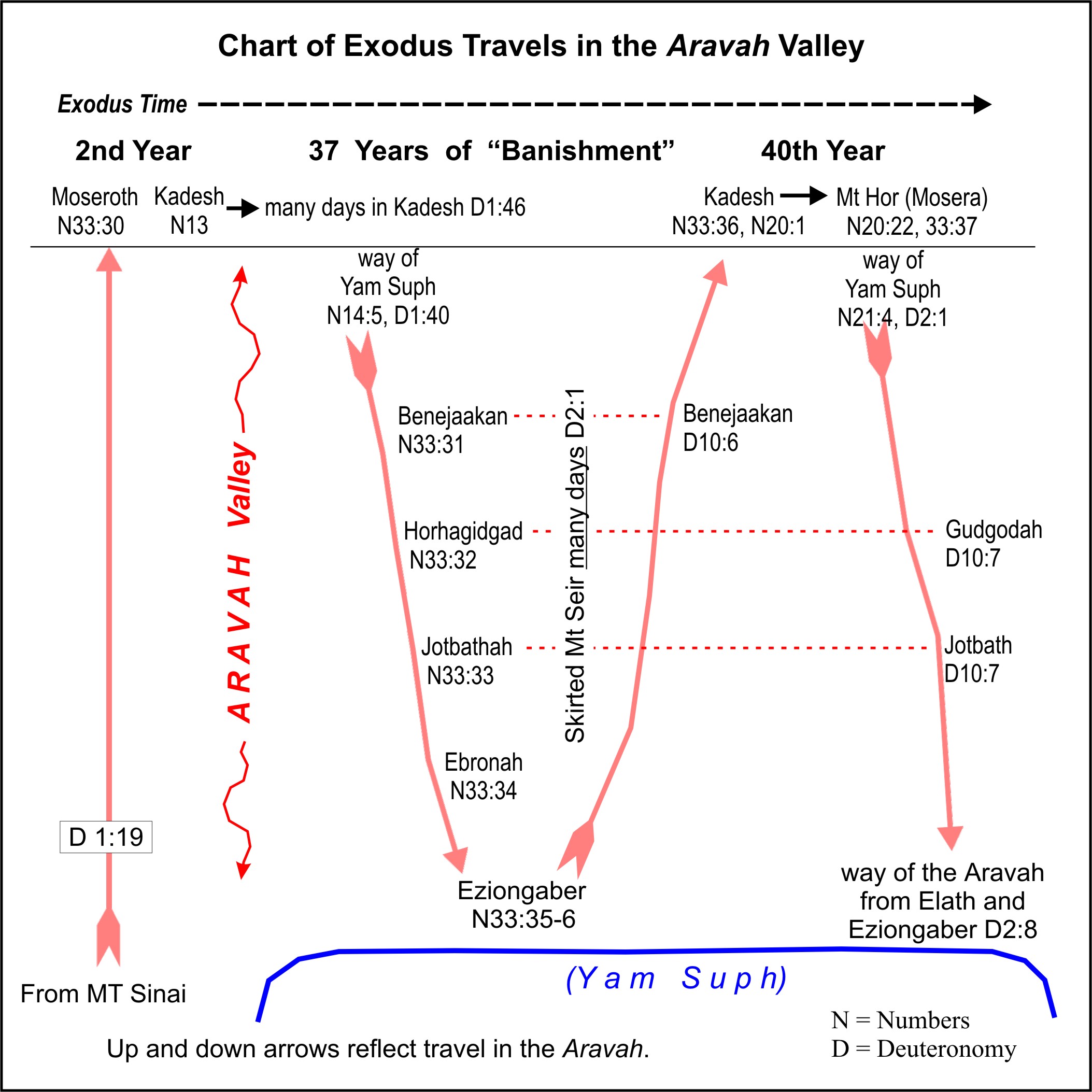

Traveling south within the Aravah, they encamped at Benejaakan, Horhagidgad, Jotbathah, Ebronah, and then Eziongaber (Num. 33:31-36). A diagram of these stops is shown in Figure 5. The position of Eziongaber at the end of this list infers a southerly movement within this corridor. The association between Eziongaber and the head of the gulf (Yam Suph) is clearly referenced in Num. 33:35-36; Deut. 2:8; 1 Kings 9:26, 22:48; and 2 Chron. 8:17, 20:36.

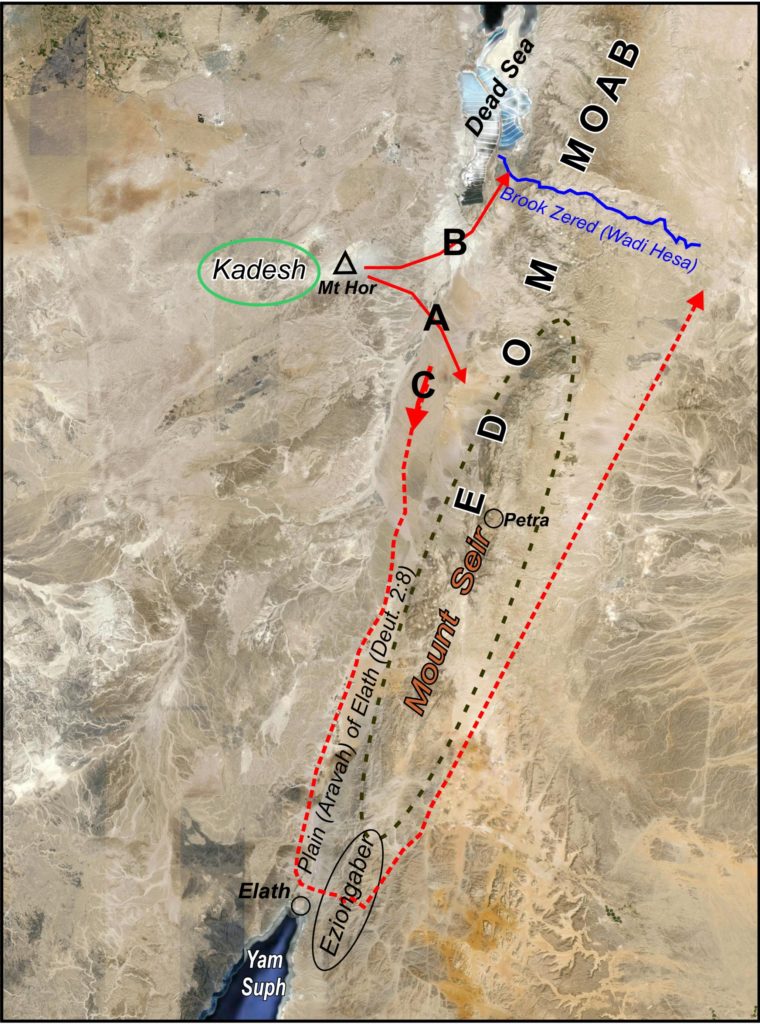

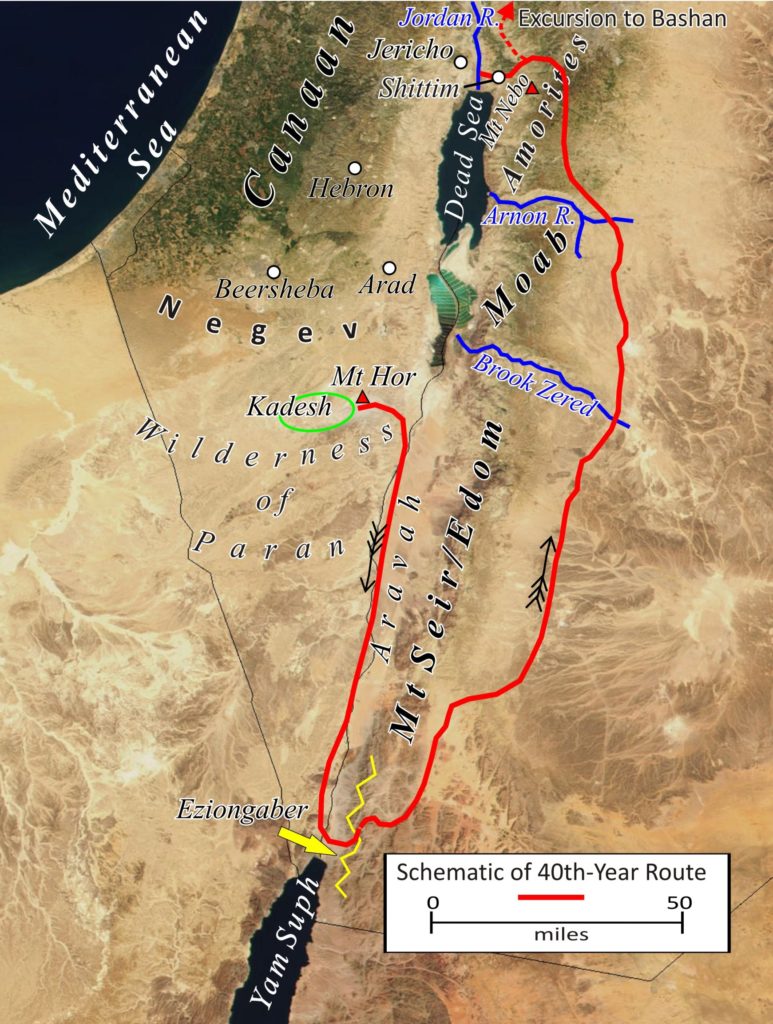

Figure 5 The Aravah Travels. Starting on the left, Kadesh was reached from Mount Sinai via the Aravah. The 37-year banishment began in Kadesh and continued with encampments in the Aravah, reaching as far south as Eziongaber at the head of the gulf (Yam Suph). The Hebrews returned to Kadesh again at the start of the 40th year. On the far right, the Hebrews bypassed Edom and Moab, traveling south in the Aravah to reach the mountain pass at the head of the gulf. The red-dashed lines highlight the three Aravah encampments that were revisited on subsequent trips (click to enlarge).

Somewhere near the end of this 37-year period, the Hebrews “…removed from Eziongaber, and pitched in the wilderness of Zin, which is Kadesh” (Num. 33:36). In this journey, an encampment is mentioned at Benejaakan in the northern part of the Aravah: “…the children of Israel took their journey from Beeroth of the children of Jaakan to Mosera: there Aaron died, and there he was buried….” (Deut. 10:6). Recall that Mosera referred to mount Hor and that Benejaakan was the first encampment reached after initially leaving Kadesh (Num. 33:31). “Beeroth [wells] of the children of Jaakan” is the Benejaakan (“sons of Jaakan”) of Num. 33:32, although worded differently by Bible translators. This journey is diagrammed in Figure 5.

In summary, the Bible gives enough information about the 37-year “banishment” period to estimate the area of travel, but deciphering the route is contingent upon identifying Moseroth (Num. 33:30) as Kadesh. This period began with a prolonged stay in Kadesh, followed by a prolonged southerly movement in the Aravah with encampments at Benejaakan, Horhagidgad, Jotbathah, Ebronah, and Eziongaber.

The multitude eventually left Eziongaber, moving north in the Aravah, stopping again at Benejaakan before reaching Kadesh. Thus, these 37 years involved seven named encampments and at least 200 mi. (320 km) of travel up and down the Aravah between Kadesh and Eziongaber. The Bible gives no hint of a journey outside of this area, or any return to the Arabia Peninsula.

8–The Start of the 40th Year–

The Hebrews re-entered Kadesh in the first month of the 40th year. Moses’ sister Miriam died there (Num. 20:1). Upon their arrival, there was no water, and they quarreled with Moses (Num. 20:2-3). The Lord told Moses and Aaron to speak to “the rock” to bring forth water, but Moses disobeyed and struck the rock twice (Num. 8-11). Due to their disobedience, the Lord chastened Moses and Aaron, forbidding their entry into the Promised Land (Num. 20:12).

From Kadesh, Moses sent messengers to Edom and Moab seeking passage through their land to reach Jericho, but they both refused (cf. Num. 20:23; Judges 11:17). This episode is illustrated in Figure 6. The Hebrews then moved en masse to the adjacent mount Hor where the entire congregation witnessed Aaron’s death on its peak (Num. 20:22, 33:37). Thirty days of mourning followed (Num. 20:29).

Figure 6 Sending messengers from Kadesh. In the 40th year, Moses sent messengers to Edom (A) and Moab (B) seeking passage through their lands in order to reach Jericho. Both refused, requiring the Hebrews to compass Edom and Mount Seir (route C) to start their northbound journey to Canaan (click to enlarge).

At that time, “…king Arad the Canaanite, which dwelt in the south [Negev], heard tell that Israel came by the way of the spies; then he fought against Israel, and took some of them prisoners” (Num. 21:1; cf. 33:40). Subsequently, the Hebrews “utterly destroyed them and their cities: and he called the name of the place Hormah” (Num. 21:3). The location of Tel Arad is shown in Figure 7.

The fact that the king felt threatened implies that mount Hor was close to the Negev (and Arad). The ruins ascribed to Arad are in the Negev, 29 mi. (48 km) NNE of Jebel Moderah, proposed here as mount Hor. This verse also implies that Kadesh was close to mount Hor because the king associated the “way of the spies” (their route from Kadesh to Canaan) with mount Hor. According to Num. 13:17 and 22, that route ascended up through the Negev.

The Hebrews then “…journeyed from mount Hor by the way of the Red sea [Yam Suph], to compass the land of Edom: and the soul of the people was much discouraged because of the way [the great distance]” (Num. 21:4). In other words, they moved southeast from mount Hor into the Aravah valley where they encamped at Gudgodah, and then “Jotbath, a land of rivers of waters” (Deut. 10:7). These places appear to be identical with Horhagidgad and Jotbathah encountered years earlier on the way to Eziongaber (Num. 33:32-33). (See the diagram in Figure 5.)

At the south end of the Aravah, near the head of the gulf, the Hebrews moved “…through the way of the plain [Aravah] from Elath, and from Eziongaber…” (Deut. 2:8) where they turned east to traverse the Wady Ithm mountain pass. This wadi, located 5.25 mi. (8.5 km) north of the gulf, was historically used to reach the eastern slopes of Mount Seir and Edom from the Aravah. Eziongaber, meaning “strong spine” (cf. Gesenius 1979, 6096, 1396c), likely referred to the spiny mountain range lying broadly east of Elath that hosted this important pass.

The Hebrews had previously used the Wady Ithm pass in the second year of the Exodus in their transit from Mount Sinai (in the Arabian Peninsula) to the Aravah valley and Kadesh. It was referenced in this description: “There are eleven days’ journey from Horeb by the way of mount Seir unto Kadeshbarnea” (Deut. 1:2). (In this text, Moses used 11 days as a measure of distance based on commercial caravan travel rates, not the pace of the Hebrew multitude.)

9–Onward to the Edom-Moab Border–

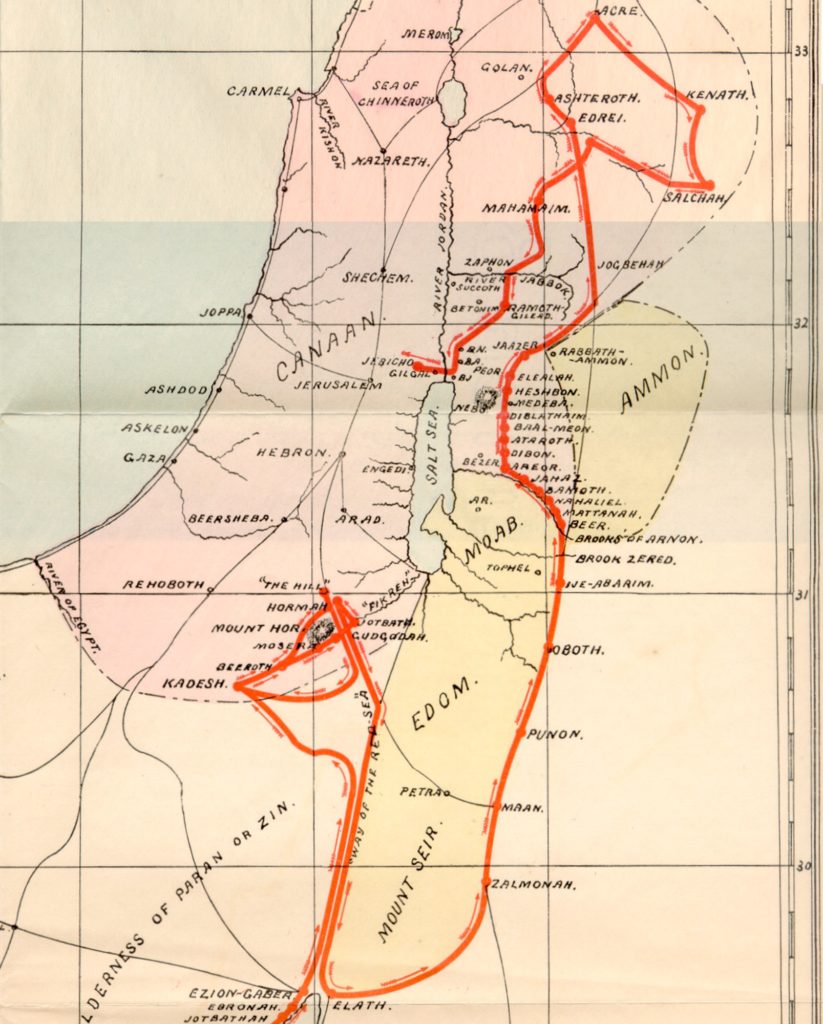

The Bible gives many particulars about the travel between Kadesh and Jericho, which lasted around nearly 11 months. The density of detail increased once the Hebrews passed by Moab (Figure 7). In fact, dozens of place names and encampments are listed in Num. 21, 33, and Deut. 2, 3, making this portion of the Exodus the best-documented and most certain. The antique map in Figure 8 illustrates one of many attempts to reconstruct this phase of the Exodus.

Figure 7 The Route between Kadesh and Canaan. The northerly excursion into Bashan, which extended 55 mi. further north to Edrei, is not shown (click to enlarge).

Figure 8 An antique map depicting the surmised Exodus route to Canaan. Note the many place names that are listed after Moab was passed (from Auchincloss 1906) (click to enlarge).

After Aaron’s death and a month of mourning (Num. 20:29), “they journeyed from mount Hor by the way of the Red sea [Yam Suph], to compass [skirt] the land of Edom…” (Num. 21:4). Deut. 2:1-3 reiterates:

Then we turned and took our journey into the wilderness by the way of the Red sea [Yam Suph], as the LORD spake unto me: and we compassed mount Seir many days. And the LORD spake unto me, saying, Ye have compassed this mountain long enough: turn you northward.

The Hebrews were forced to bypass Edom, the descendants of Esau who lived in Mount Seir (Deut. 2:4), because the Edomites refused passage through their land (Num. 20:14-21). Today this region is the southern part of modern Jordan.

After reaching the east side of the mountains of Edom, their track north to Moab included these encampments: Zalmonah, Punon; Oboth (Num. 33:41-43). Somewhere before reaching Oboth, the people reviled Moses and “the LORD sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died” (Num. 21:6). “Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived” (Num. 21:9). They then encamped:

at Ijeabarim (Num. 33:44), in the wilderness east of Moab (Num. 21:11) in the valley of the brook Zered (Num. 21:12, Deut. 2:13-14)

The brook Zered marked the boundary between Edom and Moab (Figure 7). Its crossing was noted by Moses:

…the space in which we came from Kadeshbarnea, until we were come over the brook Zered, was thirty and eight years; until all the generation of the men of war were wasted out from among the host, as the LORD sware unto them (Deut. 2:14).

After this crossing, the Hebrews were told not to meddle with the Moabites who lived between the brook Zered and the Arnon river (Figure 7).

This verse permits an estimate of the travel time taken to reach Zered. The Hebrews arrived in Kadesh 38 years earlier at the time of first ripe grapes (Num. 13:20), sometime in June. In the 40th year, they entered Kadesh in the first month (Num. 20:1), likely March/April. In Kadesh, they experienced the water from rock miracle, and sent messengers to Moab and Edom. Then they traveled to Mount Hor for Aaron’s death, followed by a month of mourning. Hence, they may not have left Mount Hor until near the end of May.

Since they arrived at the brook Zered at the time of first ripe grapes (e.g., late June?), one could estimate that they had a maximum of a month’s travel from Mount Hor to that point. The approximate distance is 225 mi. (360 km), meaning an average of 7.5 mi./day without any encampments. However, three encampments are listed, Zalmonah, Punon; Oboth, and there were likely some unlisted encampments. Thus, the average mileage on travel days may have been 10-15 mi. (16-24 km).

10—North to Jericho–

Continuing to the north, they crossed the Arnon river, located about 35 mi. (56 km) north of the brook Zered. The Arnon was the border between Moab and the Amorites (Num. 21:13; Deut. 2:24). Then at Beeroth (meaning “wells”), there was another miraculous provision of water (Num. 21:16-18). They then encamped at Mattanah, Nahaliel, and Bamoth (Num. 21:18-20).

From Bamoth, in Kedemoth (Deut. 2:26), they sent messengers to Sihon, king of the Amorites, asking permission to pass through his land. But, he refused and assembled his army. The Hebrews defeated him at Jahaz and captured the Amorite land from the Arnon river to the Jabbok river (Num. 21:21-24), a north-south distance of 51 mi. (83 km). They also took possession of his city, Heshbon, and the surrounding towns, located in land that the Amorites had taken from Moab (Num. 21: 25-26). “Thus Israel dwelt in the land of the Amorites” (Num. 21:31).

They then encamped at Dibongad and Almondiblathaim (Num. 33:46), eventually moving to the northeast end of the Dead Sea “…in the mountains of Abarim before Nebo…and in the plains of Moab by Jordan [river] near Jericho…from Bethjesimoth even unto Abelshittim in the plains of Moab” (Num. 33:46-49). Abelshittim meaning “meadow of the acacias,” is also referenced as Shittim. This description suggests a very large area for the encampment.

Moses then sent spies north to Jaazer, eventually driving out the Amorites, and taking their villages (Num. 21:32). The Hebrews continued north via the way of Bashan and defeated the Amorite King Og and his people at Edrei and “possessed his land” (Num. 21:32-35). Edrei was 60 mi. (100 km) north of the Hebrew encampment at Shittim by the Jordan river. (This excursion to the north is not shown on the map in Figure 7.)

Balak, King of Moab, feared the Hebrews for what they had done to the Amorites and consulted with the Midianite elders in his region (Num. 22:2-4). He then employed Balaam, a prophet from Aram, to curse the Hebrews. But the LORD compelled him to offer blessings instead (Num. 22:5-24:25).

While encamped at Shittim, the Hebrews turned to harlotry and idol worship with the “daughters of Moab” (Num. 25:1), which included Midianites (e.g., Num. 25:6) as the Lord subsequently instructed Moses to “vex the Midianites” (Num. 25:18-19). At the direction of the Lord, the judges of Israel slew 24,000 Hebrews who had been involved in the idolatry (Num. 25:9).

Also at Shittim, Moses took a census of the Hebrew males twenty years old and up that were fit for war (Num. 26:2, 63). The total was 601,730 (Num. 26:51). A separate census of the Levite males one-month-old and up totaled 23,000 (Num. 26:62).

But among these there was not a man of them whom Moses and Aaron the priest numbered, when they numbered the children of Israel in the wilderness of Sinai.

For the LORD had said of them, they shall surely die in the wilderness. And there was not left a man of them, save Caleb the son of Jephunneh, and Joshua the son of Nun (Num. 26:64-65).

The Lord then instructed Moses: “avenge the children of Israel of the Midianites: afterward shalt thou be gathered unto thy people” (Num. 31:1-2). One thousand armed men from each tribe, for a total of 12,000, were readied for battle (Num. 31:4-5). In the fight, the five kings of Midian were slain and all the males (Num. 31:7-8). Virgins were taken captive and all their cattle and goods seized (Num. 31:9), including 675,000 sheep, 72,000 beeves, 61,000 asses, and 32,000 persons (Num. 31:32-35).

In the process of bypassing Moab and defeating the Amorites, the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh claimed territory east of the Dead Sea and Jordan river. Rueben settled in the Mishor tableland between the Arnon river and the north end of the Dead Sea (Josh. 13:15-23). Gad settled north of Reuben in Gilead on the east side of the Jordan river, extending north to the Sea of Galilee (Josh. 13:24-27). The half-tribe of Manasseh settled north of Gad in Bashan (Josh. 13:29-31). (The half-tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh descended from Joseph.) The north-south extent of these tribal territories, ranging from the Arnon river to Mount Hermon (Deut. 3:8), measured about 130 mi. (210 km).

…In the fortieth year, in the eleventh month, on the first day of the month, that Moses spake unto the children of Israel, according unto all that the LORD had given him in commandment unto them” (Deut. 1:3). The book of Deuteronomy records his restatement of the exodus events, the Ten Commandments (Deut. 5:1-21) and the Law, and his extended admonishment and blessing of the people.

Moses then asked the Lord to appoint a new leader. “And the LORD said unto Moses, take thee Joshua the son of Nun, a man in whom is the spirit, and lay thine hand upon him; And set him before Eleazar the priest, and before all the congregation; and give him a charge in their sight” (Num. 27:18-19).

Then “Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho. And the LORD shewed him…” (Deut. 34:1) all of the Promised Land allotted to the tribes (cf. Deut. 3:25-27, Num. 27:12-13). (Moses was not permitted to enter due to his own rebellion in Kadesh, e.g., Num. 27:14.)

So Moses the servant of the LORD died there in the land of Moab, according to the word of the LORD. And he buried him in a valley in the land of Moab, over against Bethpeor: but no man knoweth of his sepulchre unto this day. And Moses [was] an hundred and twenty years old when he died: his eye was not dim nor his natural force abated. And the children of Israel wept for Moses in the plains of Moab thirty days… (Deut. 34:5-8)

On the tenth day of the first month (on the eve of the 41st year), the Hebrews crossed the flooded Jordan river, aided by its miraculous parting (Josh. 3). Four days later, on the west side of the Jordan, their Passover celebration at Gilgal marked the close of the Exodus, exactly 40 years after leaving Egypt (Josh. 5:10-12). The daily provision of manna ceased the following day (Josh. 5:12).

The nearby city of Jericho soon became the site of their first military victory in the land of Canaan (Josh. 6).

11–Conclusion–

The biblical story of the deliverance of the Hebrews from Egypt constitutes one of the great dramas of the ancient world. The immensity of the multitude, likely over 1.5 million, the distance of their travel, and their needs for sustenance for forty years is difficult to fathom. At the close of his life, Moses called all Israel together and presented this summary:

You have seen all that the LORD did before your eyes in the land of Egypt, to Pharaoh and to all his servants and to all his land–the great trials which your eyes have seen, the signs, and those great wonders…And I have led you forty years in the wilderness. Your clothes have not worn out on you, and your sandals have not worn out on your feet. You have not eaten bread, nor have you drunk wine…that you may know that I [am] the LORD your God…. Therefore keep the words of this covenant, and do them, that you may prosper in all that you do (Deut. 29:2-3, 5-6, 9).

There is a penchant to focus on certain chronological and geographical aspects of this story, but the recurring theme woven into the fabric of the Exodus is one of human fallibility. Despite witnessing great miracles and wonders, plus the horrid consequences of disobedience, the Hebrews repeatedly rebelled:

- at Mount Sinai: worship of the golden calf—3000 died in judgement (Exod. 32:28)

- at Taberah: complaining—people died from the fire of the Lord (Num. 11:1-3)

- at Kibrothhattaavah: lusting—a great plague killed many (Num. 11:33-34)

- at Kadesh: rebellion—an entire generation sentenced to death (Num. 14:2, 29)

- at Kadesh: fought the Amalekites/Amorites—defeated badly (Num. 14:44/Deut. 1:44)

- at Kadesh: rebellion of Korah, et al.—over 14,700 died (Num. 16:49)

- east of Edom: rebellion—a plague of serpents and much people died (Num. 21:6)

- at Shittim: idolatry—24,000 died in judgement (Num. 25:1-9)

Yet, Moses prayed: “If now I have found grace in thy sight, O Lord, let my Lord, I pray thee, go among us; for it is a stiff-necked people; and pardon our iniquity and our sin, and take us for thine inheritance” (Num. 34:9).

–References–

Ain-Avdat. 2018. http://mosaic.lk.net/g-einavdat.html.

Auchincloss, W.S. 1906. To Canaan in One Year. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Bailey, Clinton. 1984. Bedouin Place Names in Sinai. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 116: 42-57.

Edersheim, Rev. Dr. Alfred. 1876. The Exodus and the Wanderings in the Wilderness. London: The Religious Tract Society. https://books.google.com/books?id=vg5FAAAAYAAJ&q=mount+hor#v=onepage&q=paran&f=false

Eusebius, of Caesarea; Jerome, Saint; G S P Freeman-Grenville, Rupert L Chapman, Joan E Taylor. 2003. The Onomasticon: Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D. Jerusalem: Carta.

Fritz, Glen A. 2016a. The Lost Sea of the Exodus: A Modern Geographical Analysis, 2nd ed. San Antonio: GeoTech.

Fritz, Glen A. 2016b. Fire on the Mountain: Geography, Geology & Theophany at Jabal al-Lawz (out of print). San Antonio: GeoTech.

Gesenius. 1979. Gesenius’ Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon, trans. Samuel Prideaux Tregelles. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House.

Josephus, Flavius. 1960. Josephus Complete Works, trans. William Whiston. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel.

Moller, Lennart. 2008. The Exodus Case: New Discoveries of the Historical Exodus. Sweden: Scandinavia Publishing House.

Nahal Zin. 2018. https://www.bibleplaces.com/nahalzin/.

Rahimi, Goel. 2018. Exodus: Proof & Evidence. www.epe.org.il.

Stevenson, Edward Luther, trans., ed. 1932. Claudius Ptolemy The Geography. New York: New York Public Library.

Strong, James. 1990. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Wilton, Rev. Edward. 1863. The Negeb or “South Country” of Scripture (map and book). Cambridge & London: MacMillan & Co. https://archive.org/details/negeborsouthcou00wiltgoog

https://archive.org/stream/negeborsouthcou00wiltgoog/negeborsouthcou00wiltgoog_djvu.txt