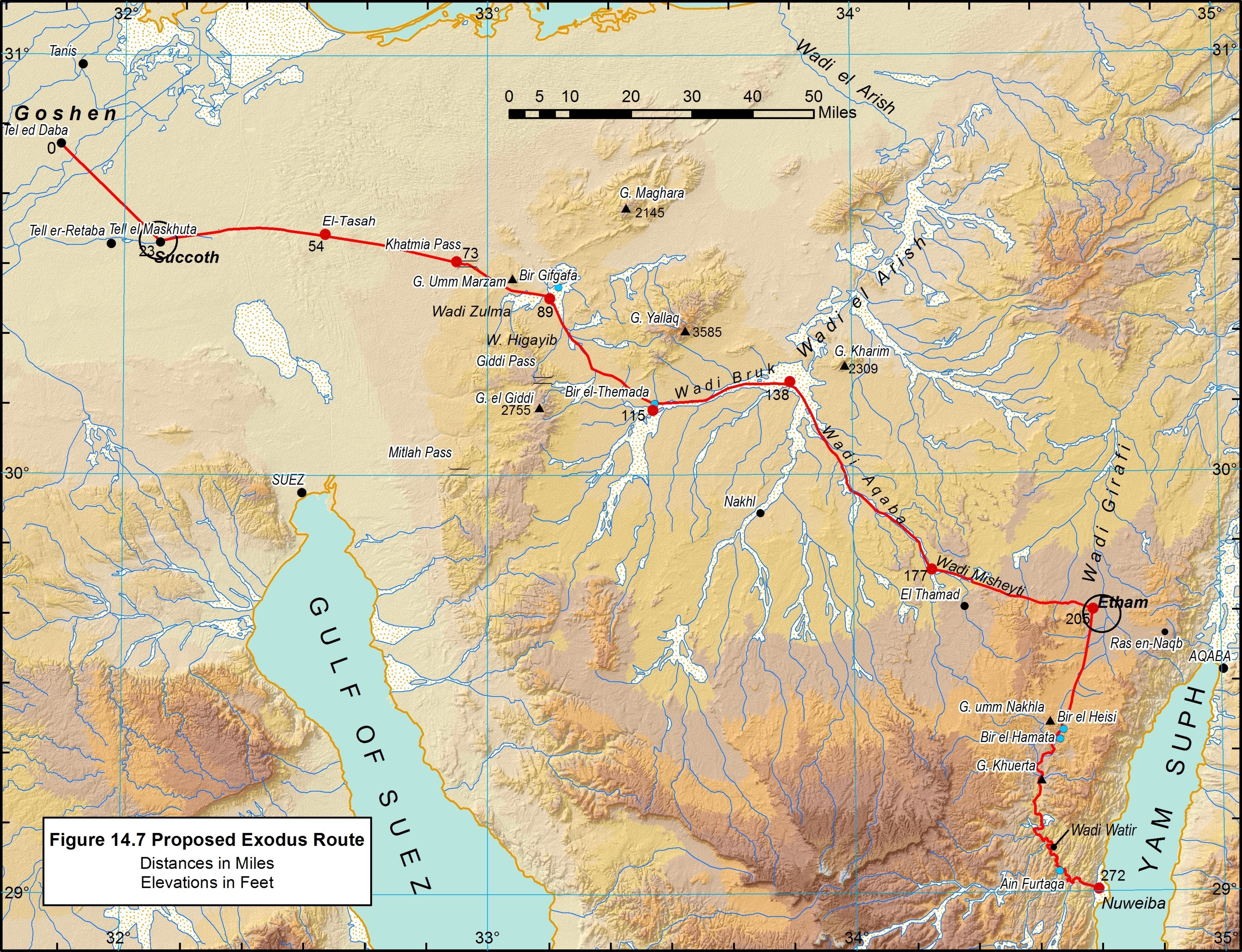

The likely starting point of the Exodus was Tel el-Dab’a (ancient Rameses), in Goshen in the northeast Nile Delta (Map 1). My research, published in The Lost Sea of the Exodus, placed the sea parting at the Gulf of Aqaba (Hebrew: Yam Suph), on the east side of the Sinai Peninsula. If so, Mount Sinai would lay further east in Arabia, and the Hebrews would have hurried through the peninsula to get there.

En route to Arabia, (Exod. 13:20; 14:2), Moses received a divine command in Etham to turn from the path that lead to the head of the gulf and, instead, enter the wilderness to encamp somewhere on its shore. The only accessible and sizeable beachhead lies near the midpoint of the gulf at Nuweiba (Map 1). Suitable seafloor topography also extends toward Arabia from that point, albeit in very deep water.

What was the likely Exodus route between Rameses and Nuweiba?

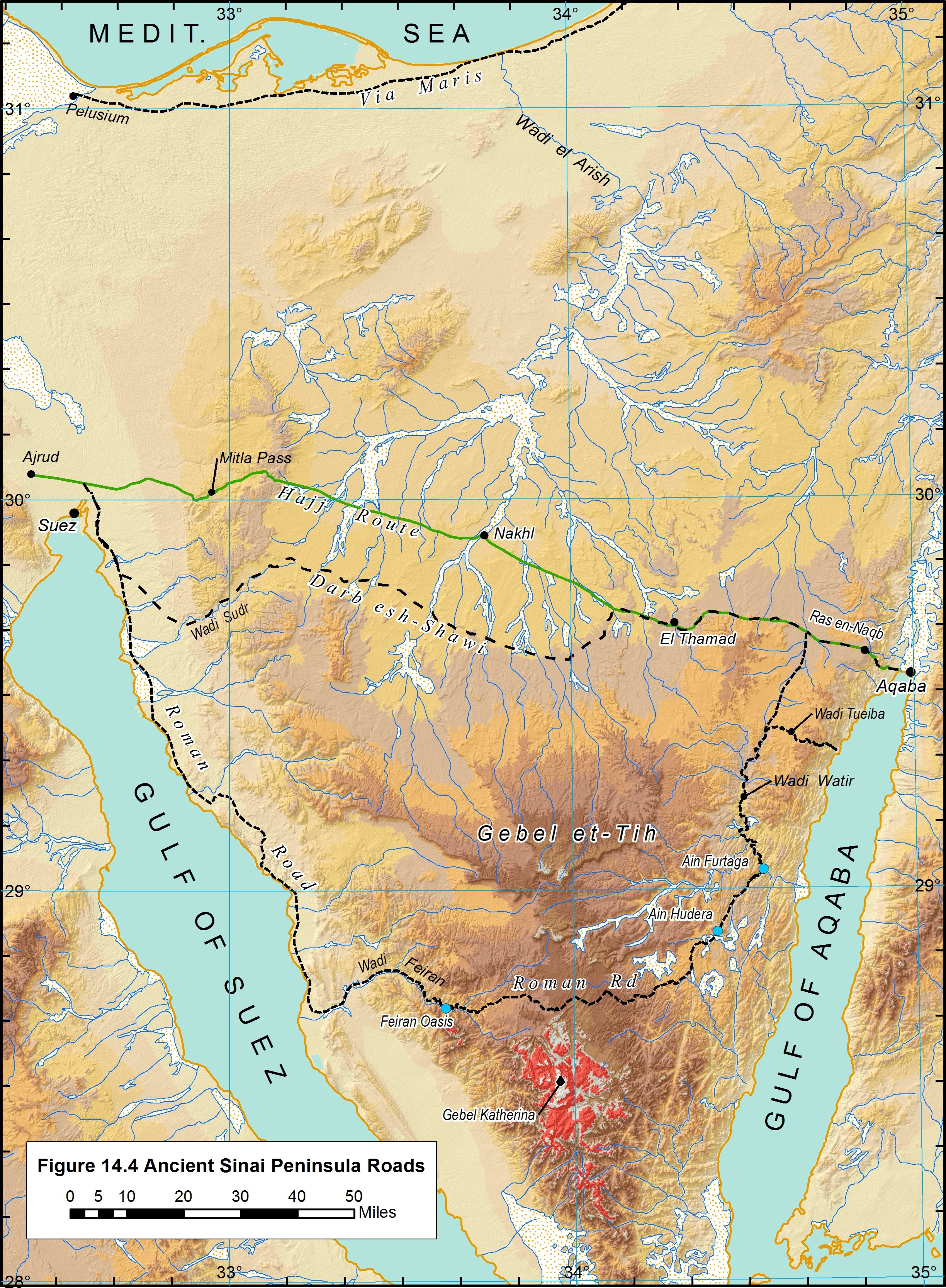

Some investigators surmise that the Hebrews followed the Darb el Hajj (Arabic: “way of the pilgrimage”), a road developed for the Muslim Hajj after the 7th-century emergence of Islam (see Map 2). The first peninsula Hajj road was constructed ca AD 875 by the Egyptian governor under the Fatimid Caliph. Much of the route lacks archaeological evidence of more ancient use. Darb el Hajjwas a general term for various pilgrim routes leading to Mecca and the Sinai Peninsula route was called Tariq al-Hajj al-Masri, meaning “the opening stage of the Hajj.” Several variations of this road developed, but the main route was always outfitted with stations provisioned in advance with water and supplies. Although this route linked the heads of the gulfs (Suez and Aqaba), it would have been a problematic path in the Exodus because it notoriously lacked water and fodder.

There are three other historical routes across the Peninsula (Map 2). The oldest, which followed the Mediterranean coast, was called “ways of Horus” by the Egyptians, and “Via Maris” (Latin: “way of the sea,” e.g., Latin Vulgate Matt. 43:15) by the Romans. The Bible called it the “way of the land of the Philistines,” but indicated that it was not used in the Exodus: “…when Pharaoh had let the people go, God led them not through the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near…” (Exod. 3:17)

The oldest route connecting the heads of the gulfs was the Darb esh-Shawi (Arabic: “way of the heights”?). It also would have presented water and fodder limitations for the Hebrews.

Further south, the Roman Road, named for its depiction on the Roman-Byzantine (4th-century AD) Peutinger Table, passed just north of the traditional Mount Sinai. Ancient Aramaic, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic graffiti along this route indicate that it was used by Nabataeans prior to the Roman period and later by religious pilgrims. This route did provide some oasis stops, but it would have added much distance to the Hebrews’ trek across the Peninsula.

My research indicates that Moses did not follow any of the above routes. The Bible says that they took “the way of the wilderness of the Red Sea (Hebrew: yam suph)” (Exod. 13:18); yam suphreferring to the Gulf of Aqaba.

The Hebrews left Egypt on the 15th of Aviv, which fell close to the Spring Equinox (March 21) and coincided with the end of the Peninsula rainy season. Arabian explorer Alois Musil (1926) observed:

If the Israelites migrated from Egypt in the month of March and if there had been an abundance of rain on the peninsula of Sinai that year, they would have found rain pools of various sizes in all of the cavities and in all of the hollows of the various river beds, and they could have comfortably replenished their water bags and watered their flocks.

Considering these factors, the best conditions would have been offered by a route utilizing the extensive wadi (valley) network in the northern peninsula plateau. Not only do these wadis offer more passable terrain, they have a greater potential for providing water and vegetation. Following this line of thinking, explorer E. H. Palmer noted that:

In the larger wadies, draining as they do so extensive an area, a very considerable amount of moisture infiltrates through the soil, producing much more vegetation than in the plains. Sufficient pasturage for the camels is always to be had in these spots, and here and there a few patches of ground are even available for cultivation (Palmer 1872).

Map 1 lays out a feasible route through the network of low-lying wadis. The travel distance between Rameses and Nuweiba via this path is about 438 km (272 mi.). Given these circumstances, and the travel chronology in the book of Exodus, I estimate that the Hebrews crossed the Sinai Peninsula in as little as 18 days, an average of 15.1 miles per day.

Consult The Lost Sea of the Exodus for more details.