Was the Biblical Exodus a Myth? According to Wikipedia, “the Exodus is the charter myth of the Israelites… it tells the myth of the enslavement of the Israelites in ancient Egypt, their liberation through the hand of their tutelary deity Yahweh…” This premise was supported by claims that the biblical Exodus account was:

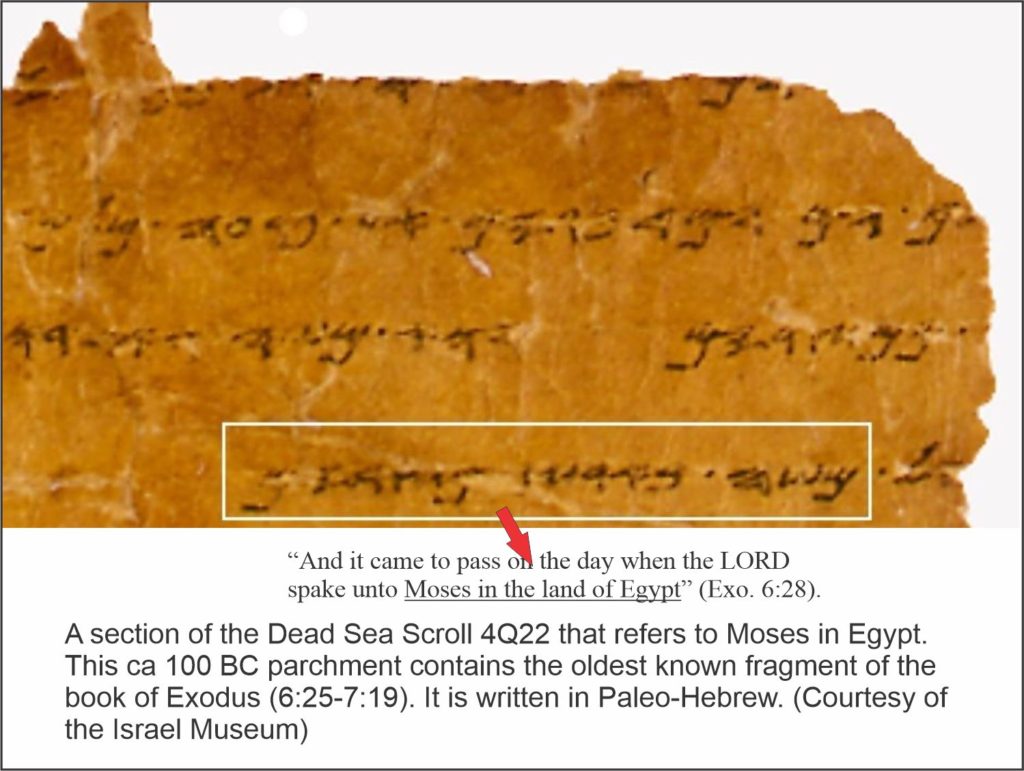

1. A Late Fabrication because the Torah (the first five books of the Bible), which claims to give an “eyewitness” account of the Exodus, was composed up to 1,000 years later.

2. Ahistorical because the story is fanciful, containing exaggerated census numbers and wonders that defy logical explanation. Also, evidence for the sojourn in Egypt, the Israelite conquest of Canaan, and Moses is lacking.

Scholarly Consensus

It is noteworthy that this article relied heavily on scholarly “consensus,” which is a form of fallacious argumentation known as the “bandwagon argument” or argumentum ad populum. The argument assumes that a proposition must be true simply because many or most people believe it. This strategy was used to identify the two main schools of thought concerning the Exodus:

A. The “majority” holds that the Exodus narrative has some historical basis, but the biblical account has little historical worth.

B. “The other main position…Biblical minimalism, is that the Exodus has no historical basis.”

But the article then added: “A third position, that the biblical narrative is essentially correct (‘Biblical Maximalism’) is today held by ‘few, if any…in mainstream scholarship, only on the more fundamentalist fringes.’” This statement seems rather prejudicial, if not ad hominem (attacking the person rather than their viewpoint).

A Late Fabrication

In its effort to malign the Exodus historicity, Wikipedia proposed that the biblical accounts were late fabrications; that the Torah was the product of unnamed redactors and editors in the 7th to 5th centuries BC, written for the purpose of building the Jewish identity. Furthermore, that the earliest traces of the Exodus tradition first appear in the 8th-century BC “northern prophets Amos (possibly) and Hosea (certainly)… [while] their southern contemporaries, Isaiah and Micah show no knowledge of an exodus.”

In response, Amos definitely acknowledged the Exodus (2:10, 3:1, 4:10), as did Hosea (2:15). In regard to the supposed silence of Isaiah and Micah, the archaeological aphorism could apply: “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” Nonetheless, Isaiah did reference the Exodus (43:16-17), as did Micah (6:45). However, Micah 6:45 was disallowed using the bandwagon argument that: “many scholars take it to be an addition by a later editor.”

But Wikipedia failed to note the earlier, more-extensive biblical Exodus references. For instance, ca. 1000 BC, King David cited the Exodus in Psalm 105 (credited to him by I Chr. 16:7:22). His mention of it is also recorded in 2 Sam. 7:18-2. Other Psalms give Exodus details, but their dating is variable: 66, 77, 78, 80, 95, 106, 107, 114, 135, and 136.

Prior to David, the book of Judges described Exodus events (11:16-22). Its writing preceded David’s 1050-1000 BC conquest of Jebus (pre-Jerusalem) because Jebus still existed in Jud. 19:10-11.

The book of Joshua, likely written ca. 1370-1330 BC, recounted the appointment of Joshua as the leader, the death of Moses, and the Israelite conquest of Canaan.

Based on its assumption that the Torah was a late fabrication, Wikipedia did not cite the wall-to-wall Exodus content in the Torah books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Nonetheless, these books name Moses 648 times and credit authorship to him in five places: Exo. 17:14, 24:4, 34:27, Num. 33:2, and Deu. 31:9, 24. In fact, much of the Torah reads like his autobiography.

Other Old Testament books named Moses 129 times and also referenced his authorship, e.g., Jos. 1:7-8, 23:6, 1 Kin. 2:3, 2 Chr. 17:9, 23:18; Dan. 9:11, 13, and Mal. 4:4. The New Testament named Moses 80 times, with Jesus, his disciples, and others linking him with the Torah on multiple occasions. Examples include John 5:46; Mark 12:19, 26; Acts 3:22, and 15:21. Although these circumstances indicate that Moses was the authority from which the Torah emanated, it does not mean that he wrote every word.

Ahistorical

In assailing the Exodus historicity, critics often elevate extra-biblical opinions above what the Bible actually says about itself. For instance, this article asserted that:

The consensus of modern scholars is that the Bible does not give an accurate account of the origins of Israel, which formed as an entity in the central highlands of Canaan in the late second millennium BCE from the indigenous Canaanite culture. [note the bandwagon argument]

In a similar vein, Kenton Sparks, quoted as calling the Exodus “mythologized history,” concluded about Mount Sinai that: “the biblical author is employing the imagery of a cosmic mountain inherited from Israel’s polytheistic Canaanite heritage” (2010, 88).

The idea that the Israelites emerged from “indigenous Canaanite culture” is at great odds with the biblical account of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the patriarchs of the 12 tribes of Israel. Abraham was divinely led from Mesopotamia to Canaan, where he and his offspring lived and worshipped the LORD (Yahweh), contrary to the polytheistic practices of the Canaanites. Geographically, the Exodus itinerary places Mount Sinai in the vicinity of the ancient land of Midian, which was far-removed from any of the “cosmic mountains” in Canaan.

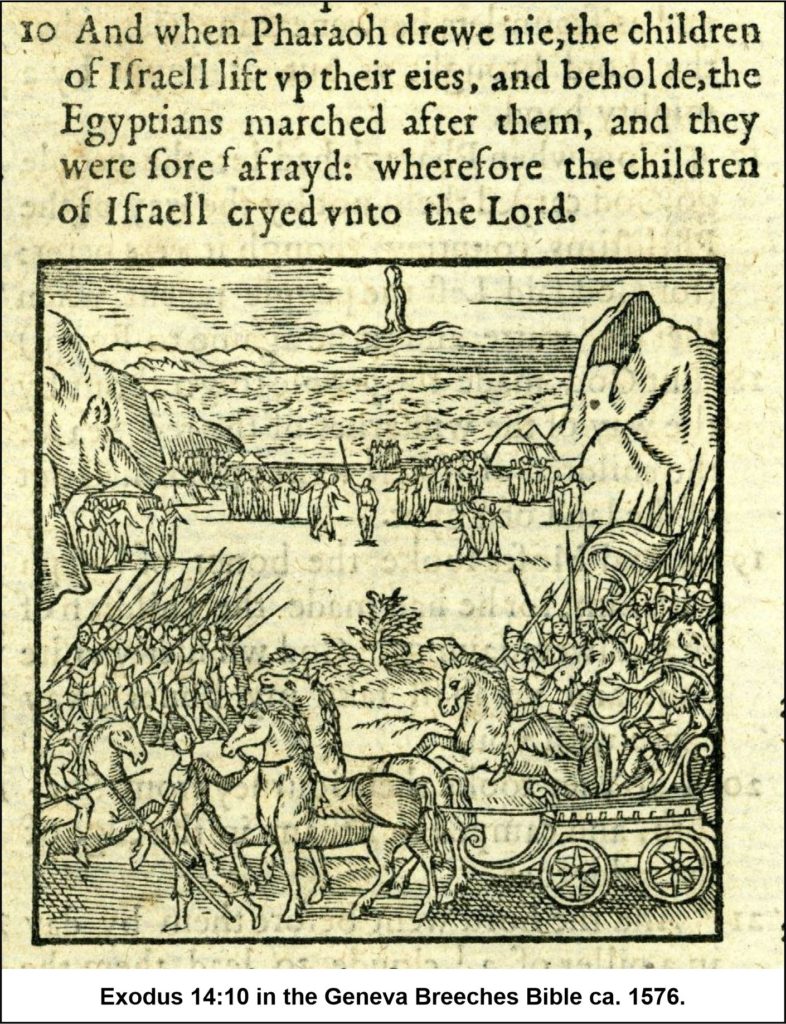

In the course of the Exodus, the Bible explains that a merciful God made numerous miraculous interventions on behalf of an undeserving, rebellious people. The most dramatic example is the Red Sea parting and the Egyptian army destruction. But Exodus critics seem to reflexively discount the miraculous, or relegate it to the mythical, turning the Red Sea into a shallow marsh, and minimizing the Israelite numbers and the distances traveled. This penchant is best explained as an a priori anti-supernatural bias, rather than problems of textual criticism, history, or archaeology.

Scholars usually approach ancient documents as “innocent unless proven guilty” of intentional fabrication or distortion, thus paralleling the rules of legal evidence. However, over the last century, some scholars began to view the biblical documents as “guilty until proven innocent”; demanding external corroboration in order to be considered historical. This treatment constitutes the “fallacy of presumptive proof,” which occurs “when a party advances a proposition and then shifts the burden of proof or disproof to others [in this case, the biblical documents]” (Fischer 1970, 48).

In this regard, Egyptologist James Hoffmeier gave this pithy comment:

At an earlier time it was quite revolutionary to say that one should treat the Bible with the same critical eye as used for any other book. Now, it is interesting to see how many critical scholars, especially those in the minimalist camp, do not treat the Bible like any other book. Rather there seems to be a double standard that accepts the claims made in Egyptian or Assyrian texts without external proof, but demands of a biblical witness that it must be corroborated by outside sources (2005, 20).

Almost two thousand years ago, the Jewish historian Josephus addressed the question of the historicity of the Hebrew Scriptures:

…But now as to our forefathers, that they took no less care [than the Egyptians and Babylonians] about writing such records…and that these records have been written all along down to our own times with the utmost accuracy… (Against Apion I.6). [We] only have twenty-two books, which contain the records of all the past times; which are justly believed to be divine; and of them, five belong to Moses…. During so many ages as have already passed, no one has been so bold as either to add anything to them or to make any change in them… (ibid. I.8).

Josephus further noted that this belief was so strong among the Jews of his day that they were willing to die for their writings, unlike the Greeks, who would not be willing to die for any of their works (ibid.).

Conclusion

Was the Exodus a myth? According to Wikipedia, “scholarly consensus” says yes based on (1) the late fabrication of the Exodus accounts and (2) the fantastic stories that they contain.

But looking more closely, disparagement of the Exodus actually involves two types of objections: (1) historical and (2) philosophical. It is one thing to question the authenticity of ancient documents, the veracity of the writers, and implications of archaeological findings. It is another thing to automatically discount them because they describe miracles and an omnipotent God dealing with mankind. Much of the Exodus criticism may be rooted in philosophical objections, but scholars instead focus on historical objections because they are more intellectually palatable.

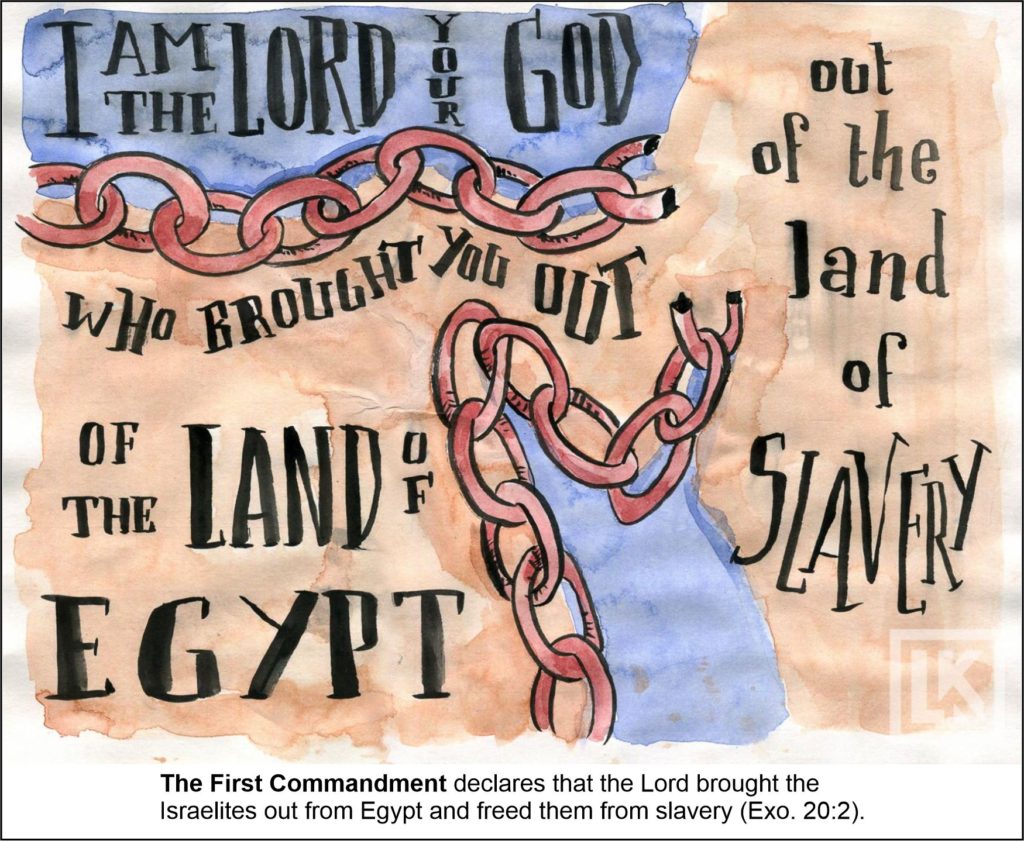

Some philosophical objections may boil down to the question: “Indeed, has God said?” (Gen. 3:1 NASB), which was first uttered by the serpent in the garden of Eden. In the Jewish tradition, the First Commandment reads: “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage” (Exo. 20:2). In order to consider the Exodus a myth, this commandment (and those that follow?) must seemingly be disregarded.

If it is truly obvious to “most scholars” that the biblical account is unreliable and the Exodus was a myth, it seems nonsensical to waste academic resources slicing and dicing the story just to reiterate a forgone conclusion.

References

Fischer, David Hackett. 1970. Historians’ Fallacies. New York: Harper & Row.

Hoffmeier, James K. 2005. Ancient Israel in Sinai. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sparks, Kenton L. 2010. Genre Criticism. In Dozeman, Thomas (ed.). Methods for Exodus. Cambridge University Press.