Passover—A night different from all others—

Stepping back in time over 3400 years, the sons of Israel (Jacob) had been enslaved in Egypt for decades. Nine plagues had already befallen Egypt, and the prideful Pharaoh had still not relented to free the Hebrews and let them depart from Egypt.

The first Passover feast marked the beginning of the 10th and final plague, which would eclipse all others. It was celebrated on the 14th of Aviv (Abib), the first month of the Hebrew calendar (Exodus 12:6). Aviv began about the time of the Spring Equinox on March 21st. The month later became known as Nissan on the Jewish calendar.

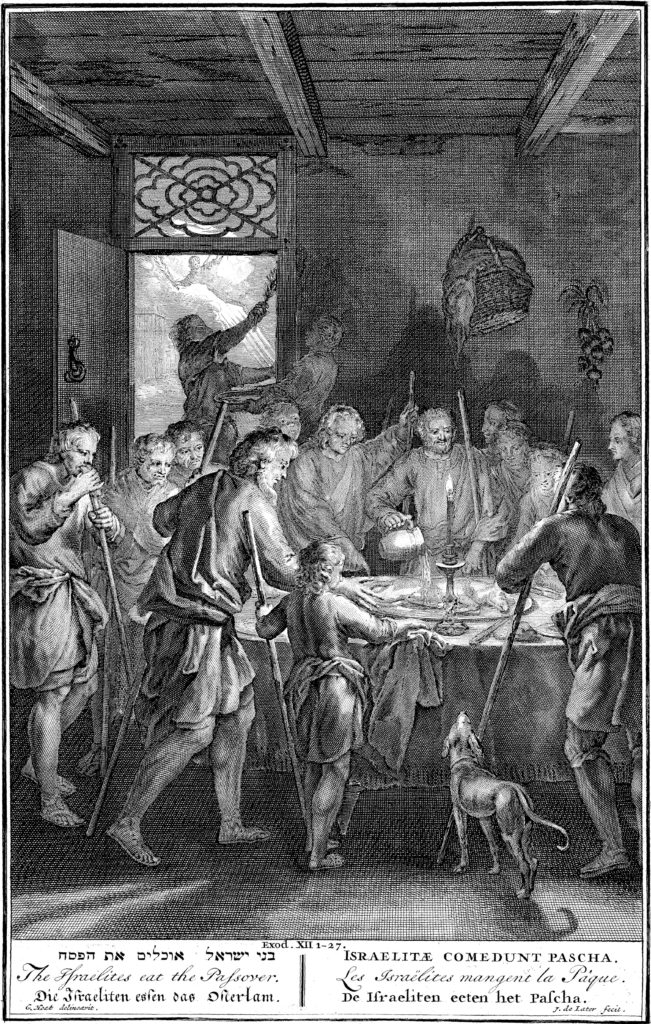

In preparation for this feast, each household was to take a first year male lamb or goat without blemish into their homes on the 10th of Aviv. Imagine the delight of the children to have a cuddly, innocent creature living in their midst. But, on the eve of the 14th, the lamb was to be slain and its blood painted on the doorposts. It was then to be roasted and eaten in haste, with the people shod and ready for travel.

Later the night, the Lord “passed over” the houses with blood on the doorposts. But, for the Egyptian homes that lacked the blood, the firstborn males of all men and beasts died. On the morrow, the anguished Pharaoh immediately thrust the Hebrews from Egypt, which initiated the Exodus.

The Hebrew word for Passover, Pesakh, is first mentioned in Exodus 12:13. The word Exodus never occurs in the Hebrew Bible. It only appears in non-Hebrew translations as the title of the second book of the Torah. It comes from the Latin “Exodus,” or the Greek “Exodos.” The name of the book of Exodus in Hebrew is Shemot, meaning “names.” Shemot is the second word in Exodus 1:1, which begins the listing of the descendants of Israel. The modern Hebrew term meaning Exodus is pronounced yetziyah.

At the first Passover, the Lord commanded that:

“…this day shall be unto you for a memorial; and ye shall keep it a feast to the LORD throughout your generations; ye shall keep it a feast by an ordinance forever.” (Exodus 12:14)

“…ye shall observe this thing for an ordinance to thee and to thy sons forever. And it shall come to pass, when ye be come to the land which the LORD will give you, according as he hath promised, that ye shall keep this service.” (Exodus 12:24-25)

There are sporadic later mentions of the passover celebration in the Old Testament, and in New Testament times as well. In effect, this feast symbolizes the shedding of innocent blood to spare flawed humans from divine judgement. To Christians, Passover presaged the ultimate fulfillment by Jesus, the “lamb of God” (e.g., John 1:29), Messiah, “our passover lamb who is sacrificed for us” (1 Cor. 5-7).

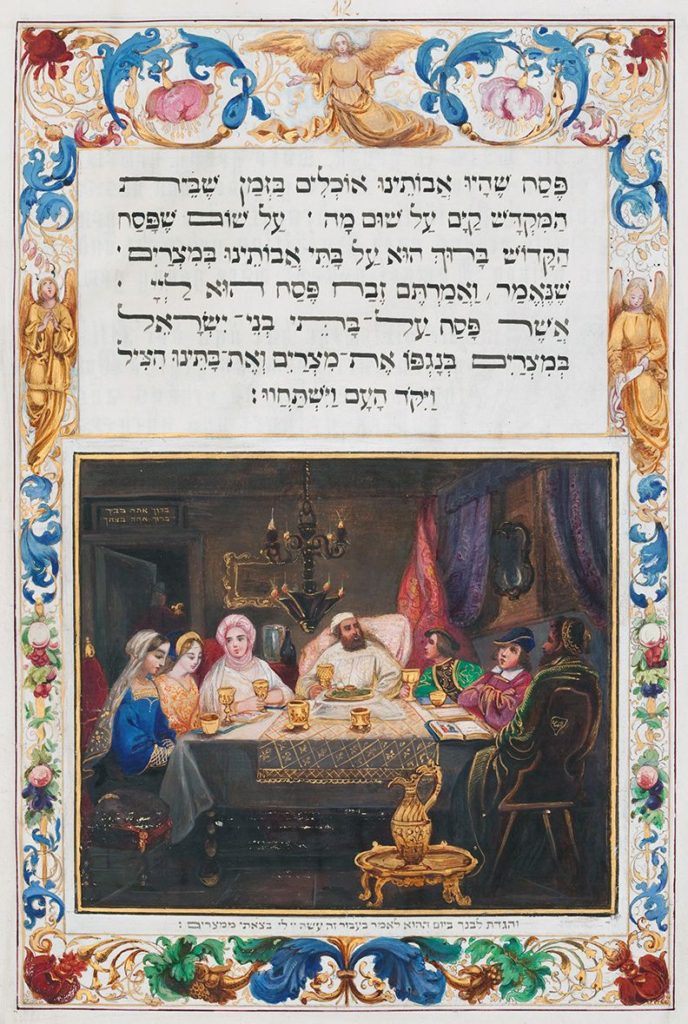

In accordance with the original divine directive, Jewish people all over the world throughout the centuries have celebrated Passover, whether under conditions of distress and dearth, or prosperity and liberty. The Passover meal is called the Seder, a Hebrew word meaning “order.” The order of the celebration is guided by the Haggadah (meaning “the telling”), a text that facilitates the retelling the story of the Exodus from Egypt.

The oldest source prescribing a Passover Seder is the Mishnah (a part of the Talmud), which dates to about AD 300. The earliest surviving Haggadah manuscript, discovered in the Genizah of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in old Cairo, is from the 8th century AD. It is strikingly similar to Haggadahs in modern use. The Mishnah features several questions about the relevance of the Seder foods to the Exodus. The overriding question is: “Why is this night different from all other nights?”

The longstanding Passover celebration, and the existence of the nation of Israel, are cultural phenomena that defy explanation apart from the biblical account of the Exodus. The 2020 Passover begins Wednesday evening, April 8th.