Glen A. Fritz ©2010, 2016

Introduction

And Moses stretched out his hand over the sea;

and the LORD caused the sea to go [back] by a strong east wind all that night,

and made the sea dry [land], and the waters were divided (Exod. 14:21 KJV).

Numerous Bible verses describe the parting of the Exodus Sea as a divinely orchestrated, miraculous event. The wind has often been credited as the mechanism employed to split the sea. Extending this thought, some Exodus commentators have attempted to explain the event apart from specific divine action. As a result, various Exodus scenarios have developed that route the Hebrews through shallow water venues that could reasonably be affected by wind conditions.

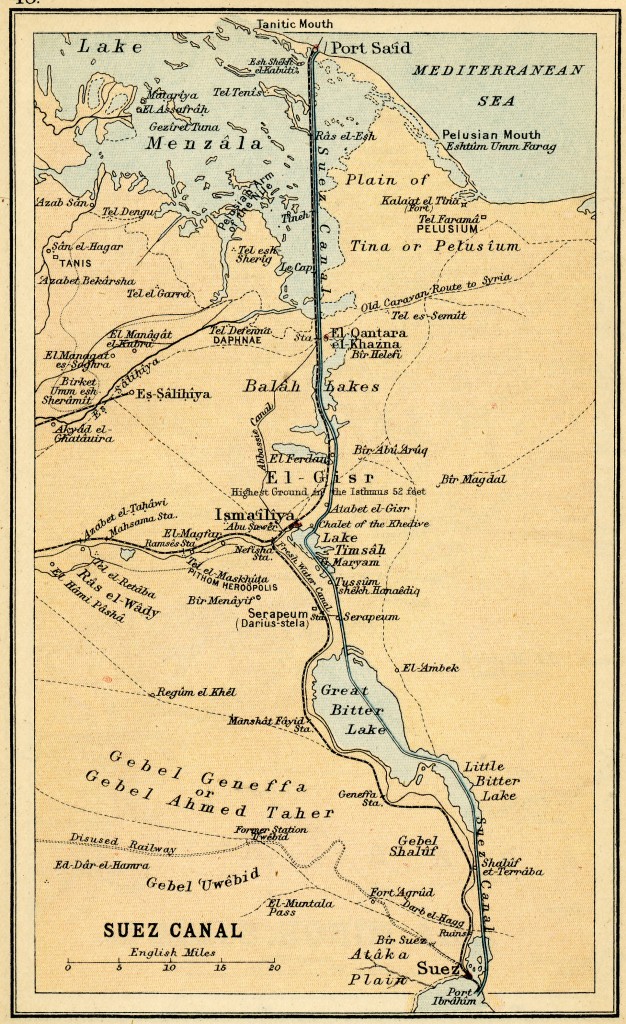

For instance, Har El (1983) placed the crossing at the Great Bitter Lake in the southern Isthmus of Suez (see Figure 1). He proposed that the crossing occurred at a ridge in the lake estimated to have been less than four feet deep, which was exposed by a southeast wind (ibid. 351). However, the Bitter Lakes were created on March 18, 1869 (Nourse 1884) when they were flooded with sea water during the construction of the Suez Canal. There is no evidence that they existed during the time of the Exodus (Fritz 2006).

Figure 1. A 19th-century map of the Suez Canal in eastern Egypt. The canal traverses the Isthmus of Suez, linking the Mediterranean Sea with the Gulf of Suez.

Humphreys (2003) proposed a crossing site 160 miles to the east at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, at an ancient marsh where the city of Eilat now stands. He assumed that these marsh conditions were created by higher sea levels during the Exodus (ibid. 197). However, the high sea level proposition is not borne out by geological or archaeological data (Fritz 2006, 2016). For example, 3000 years ago at Dor, Israel, the Mediterranean Sea was about 1 meter lower than the modern sea level. Around 4000 years ago, the sea was 2 meters lower (Sneh and Klein 1984).

Nof and Paldor (1992, 1994) analyzed wind conditions needed to produce an Exodus crossing scenario at the head of the Gulf of Suez. They calculated that sustained northwest winds of 20 meters per second (44.7 mph) could have caused a wind setdown, pushing the water over a kilometer away from the shore, and producing a local sea level drop of more than 2.5 meters. However, they admitted that the wind was not from the east, as indicated in the Bible, and that the “walls of water” of Ex. 14:22 could only be envisioned if a land ridge had existed within the setdown area.

A similar examination of a crossing site in the Isthmus of Suez was done by Hellstrom (1950), under the assumption that it was covered by the sea during the Exodus. However, as mentioned above, the elevated sea levels envisioned by Hellstrom are not supported by the historical data.

Evaluating the Wind Question

Despite the traditional focus on the wind, the underlying question is whether the Bible really attributes the sea parting to the wind. If so, was the wind natural or supernatural? What physical factors pertaining to the sea and the wind need to be taken into consideration?

The Supernatural Component

There are a variety of biblical texts that infer that the parting of the sea was a divine action. For instance, Exod. 15:12 declares, “Thou [the Lord] stretchedst out thy right hand, the earth swallowed them [the Egyptian army].” Isaiah 51:10 (NASB) asks, “Was it not You who dried up the sea, The waters of the great deep; Who made the depths of the sea a pathway For the redeemed to cross over?”

The biblical narrative “clearly intends to relate a miraculous event, and whoever attempts to explain the entire episode rationally [naturalistically] does not in fact interpret the text but projects his own ideas in place of those expressed by scripture” (Cassuto 1997, 168).

Physical Factors to Consider

The Nature of the Biblical Sea

The biblical qualities ascribed to the Exodus Sea suggest a substantial body of water that would require immense wind forces to produce any sizable displacement. Whether one argues that a fortuitous natural wind parted the sea, or that a supernatural wind performed all of the work, the scale of the sea relative to the potential wind dynamics is very problematic.

The Bible explains that the Hebrews’ sea crossing involved a sea named Yam Suph [1]. The early Greek Septuagint translators (ca. 250 BC) equated Yam Suph with their concept of the Red Sea, which always referred to a true sea, never to an inland marsh or lake, or any other small body of water.

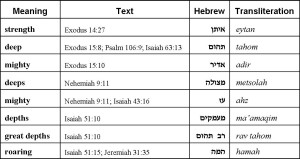

The biblical Hebrew descriptors of Yam Suph indicate that it was deep. For instance, the Lord rebuked Yam Suph, “…and it was dried up: so he led them through the depths [tahomot], as through the wilderness” (Psalm 106:9 KJV). In this passage, tahomot (singular tahom) is associated with the idea of great depths, an abyss, or great quantities of water (Gesenius 1979, #8415). The same term appears in Isaiah 51:10 (KJV): “Are You not the One who dried up the sea, the waters of the great deep [rav tahom]….” This verse then mentions that “…the depths [ma’amaqim] [2] of the sea” were made into a road “for the redeemed to cross over,” adding the sense of “deep” or “profound” (Gesenius 1979, #6009). A list of biblical Yam Suph descriptors is presented in Table 1.

Then, there is the idea of walls of water. “The people of Israel went into the midst of the sea on dry ground, the waters being a wall [khomah] to them on their right hand and on their left” (Exod. 14:22 RSV). The Hebrew word khomah, which appears 133 times in scripture, refers to “generally the wall of a town…rarely of other buildings” (Gesenius 1979, #2346). This usage pattern suggests that the height of the walls of water was not insignificant. A similar idea is expressed in Psalm 78:13 (NKJV): the Lord “…divided the sea and caused them to pass through; and He made the waters stand up like a heap.”[3]

Wind Mechanics

Overall, the biblical account of the sea crossing poses difficulties for the proposition that an east wind was the sole mechanism of its parting. Here are some considerations:

1. Ample Velocity: The wind forces would need to be adequate to both displace the sea and to sustain the walls of water on the large scale described in the Bible.

2. Maximal Velocity: The wind strength could not be so great as to hinder the passage of the Hebrews or the Egyptian army. The wind theories usually note that the wind blew all night long (per Exod. 14:21), which presumably provided time for the water displacement. Yet, they are not quick to acknowledge that the Hebrews crossed the parted sea during this same night. The event ended when the Lord instructed Moses to lift his hand over the sea and “the sea returned to his strength when the morning appeared” (Exod. 14:27). [4]

3. Wind Direction: A single wind direction would not readily exert force in the multiple vectors needed to sustain a lengthy, walled path.

4. Misguided Geographical Priorities: Instead of seeking the location of Yam Suph on the basis of its biblical geographical context, supremacy has often been given to the topographical settings with shallow bodies of water deemed suitable for the wind theories. Here is an example of this sort of misplaced focus:

“…If we believe that a passage was miraculously made for the Israelites it is useless to look for a suitable spot, for it might have happened anywhere. On the other hand, those who believe that the Israelites reaped the advantage of a natural phenomenon so impressive as to appear to them in their circumstances miraculous have met with little success in trying to find a spot where an east wind could have produced the effect attributed to it” (Peet 1923, 144).

Such methodology has produced some untenable geographical frameworks for the Exodus route. The emphasis on wind theories has also contributed to the popularity of the Reed Sea notion, in which the Exodus crossing is assigned to shallow swamps [5] that could conceivably be affected by wind conditions. Even though some commentators allow for a degree of divine guidance or timing, natural mechanisms have generally been substituted for the miraculous. In fact, the anti-supernatural view has come to dominate the literature:

“Authors today generally agree that natural phenomena were employed by divine providence at the crossing. The occurrence is not isolated in history. From classical sources we learn of the winds that drove back the waters of the lagoon and thus enabled Scipio to capture New Carthage. The text itself informs us of the part the wind played in facilitating this crossing for the Hebrews through the shallow waters of the Sea of Reeds” (Brown et al 1968, 54).

Challenging the Wind Theory

The wind theories and traditions stem from two verses.

…The LORD caused the sea to go [back] by a strong east wind all that night, and made the sea dry [land], and the waters were divided (Exod. 14:21 KJV, emphasis mine).

At the blast of thy nostrils the waters piled up, the floods stood up in a heap; the deeps congealed in the heart of the sea (Exod. 15:8 KJV).

Exodus 14:21

The important word in this verse is the preposition by. In English, it could be presumed that the wind was the agent of the parting. Perhaps this is what the early translators intended to convey.

The entire verse, worded more literally from the Hebrew, says “the Lord yolek [caused to go] the sea, b’ruakh [with wind], east, strong, and made the sea to dry and divided the waters.” There are three verbs/actions listed. The sea was: a) caused to go [yolek], b) made to dry, and c) divided. The question here is whether the text is telling us that the wind was the agent of one or more of the actions, or perhaps, not an agent at all.

In Exod. 14:21, the Hebrew b (beth, ) is prefixed to ruakh,[8] the word meaning wind [9]. The beth prefix is a preposition with a variety of potential meanings: in, among, within, at, on, near, and with. With the exception of the NIV, which used “with,” Bible translators usually supply the meaning of “by.” But, there is a problem with this use of “by.” The authoritative Gesenius’ Lexicon explains the Hebrew meaning of by only in terms of “nearness,”[10] and not as a “causative.” The idea of “nearness” does not fit well in this passage.

The more suitable meaning of this beth preposition is with. Gesenius (1979, 98-99) explains that the Hebrew idea of with can apply in two different ways: 1) of the instrument, or 2) of accompaniment. His example of the instrument usage is “with the sword” (b’kherev), meaning that the sword was the agent performing an act. Conversely, the accompaniment sense is passive, that is, a sword could be with (carried by) a man, but not used as an instrument.

Gesenius further states that the accompaniment condition especially applies “when placed after verbs of going,” which “gives them the power of carrying…, to come with anything, i.e., to bring it” (ibid. 98-99). In Exod. 14:21, the beth preposition follows the common verb yalak [11], meaning to go, lead, carry, or walk (Gesenius 1979, #3212). This situation exactly matches the grammatical condition cited by Gesenius, which strongly suggests that the wind accompanied the movement of the sea, but was not the instrument of the movement.

Exodus 15:8

The phrase “at the blast of thy nostrils the waters piled up” pictures wind (ruakh) coming from God’s nostrils (apheyka), perhaps implying that wind was the instrument. However, two things need to be clarified that make this possibility unlikely. First, this text is in a poetic section that employs anthropomorphism to describe God’s actions.

Secondly, “nose” (aph) is a common Hebrew idiom for anger or wrath. It also appears as a metonymy for “countenance” (Gesenius 1979, 69, #639 (3)). These observations are taken into account by Young’s Literal Translation of Exod. 15:8, which states, “by the spirit of Thine anger have waters been heaped together….”

The identical anthropomorphic imagery of the wind and the nose occurs in the book of Job, which has nothing to do with the sea parting event: “by the blast of God they perish, and by the breath of his nostrils are they consumed” (Job 4:9 KJV). Thus, it is unlikely that Exodus 15:8 is ascribing the sea parting to a wind mechanism. However, it is crediting it to an act of God.

Conclusion

The assumption that an east wind was the sole instrument of the sea parting boils down to the interpretation of a single beth in Exod. 14:21. In this verse, the Hebrew grammatical pattern indicates that the wind accompanied the event, but was not the instrument of the parting. As a practical matter, wind phenomena would be expected from the inrush of air into the void created by the displacement of great volumes of water causing changes in atmospheric pressure gradients.

Alternatives to the Wind Theory

Excepting the Exod. 14:21 and 15:8 verses just discussed, other biblical references to the crossing do not focus on the wind. Overall, the references to this event imply that it was immense and complex, exhibiting both meteorological and geological phenomena.

Such circumstances resonate in the stern reminder to the Hebrews in Psalm 106:22, to remember the “fearful” things that happened at Yam Suph. Earlier, Psalm 77 provided some of the fearful details:

With your mighty arm you redeemed your people…

The waters saw you, O God…and writhed;

The very depths were convulsed.

The clouds poured down water,

The skies resounded with thunder …

Your thunder was heard in the whirlwind,[12]

Your lightning lit up the world;

The earth trembled and quaked.

Your path led through the sea, .

Your way through the mighty waters,

Though your footprints were not seen.

You led your people like a flock

By the hand of Moses and Aaron. (Psalm 77:15-20 NIV, underlining for emphasis)

Earthquakes are also mentioned in another Psalm: “The sea…fled, the mountains skipped like rams, the little hills like lambs. What [ailed] thee, O thou sea, that thou fleddest?” (Psalm 114:3-5). Seismic activity could have been induced by the relatively sudden unloading of millions of tons of water from the seabed. The Gulf of Aqaba is already located in a seismically active zone, and cradled within a transform fault hosting several fault blocks (Ben-Avraham 1985, Ben-Avraham and Von Herzen 1987).

Sea turbulence, i.e., “the waters…writhed; the very depths were convulsed” (Psalm 77:16 NIV), may have killed some large sea life: “Thou didst divide the sea by thy strength: Thou brakest the heads of the sea-monsters in the waters” (Psalm 74:13, ASV).

The frightful scene at the crossing was also described by the Jewish historian Josephus:

“As soon…as…the whole Egyptian army was within it, the sea flowed to its own place, and came down with a torrent raised by storms of wind, and encompassed the Egyptians. Showers of rain also came down from the sky, and dreadful thunders and lightning, with flashes of fire. Thunderbolts also were darted upon them…” (Josephus 1960, Antiquities II.xvi.3).

Josephus also noted that the Egyptians did not know they were entering the seabed: “…but the Egyptians were not aware that they went into a road made for the Hebrews, and not for others and thus did all these men perish…” (Josephus 1960, Antiquities II.xvi.3). This circumstance suggests that the seabed matched the consistency of the shore and that they were not aware of the walls of water. The latter point may indicate that the path in the sea was much wider than the formation of the Egyptian army and/or that the visibility obscured the conditions.

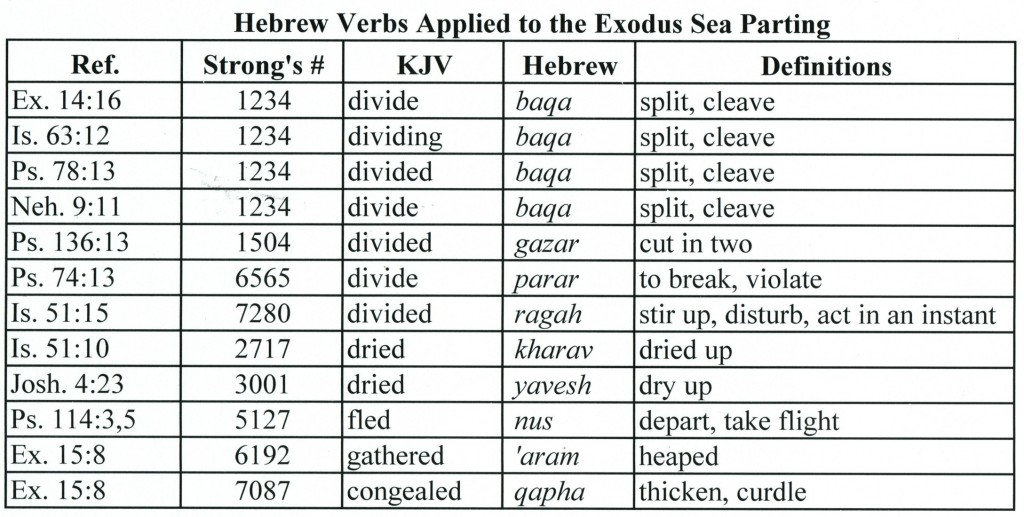

While there is one biblical reference to wind at the sea crossing, the Bible uses a multitude of verbs to describe the parting of the sea that do not necessarily involve wind. Table 2 lists nine different verbs that were used to depict the process. Baqa, meaning to split or cleave, is used most frequently. The verb ragah in Isaiah 51:15 may denote an instantaneous change. Thus, while we may not understand the manner in which the natural laws were divinely utilized or circumvented, there are a variety of scriptures that describe results without mandating a unique wind.

Summary

The traditional understanding that the wind parted the sea hinges on the interpretation of one letter of one verse. In that instance, there are sound grammatical reasons to conclude that the wind merely accompanied the event and was not a cause. The complexity of the event, and the Bible’s use of descriptors and verbs that are not necessarily dependent on wind, point to factors beyond a simple east wind.

Final Conclusions

The envisioned wind mechanism is a simplistic tradition that has done an injustice to the size and scope of the event, especially where the miraculous has been removed by commentators.

Grammatically, the Hebrew wording and context pertaining to the sea parting indicates that the wind was incidental and not instrumental. It is a logical fallacy to claim that two events have a cause-and-effect relationship simply because they occurred simultaneously. “Correlation does not imply causation.”

The biblical description of the sea parting places it in the category of the miraculous in every sense of the word. By definition, a miracle bypasses the known laws of physics, which makes it difficult to cite a particular physical mechanism. However, the many phenomena associated with the parting (e.g., thunder and lightning) seem to have occurred within the laws of nature, perhaps as a result of atmospheric changes. However, these phenomena, along with the accompanying east wind, need to be separated from the miraculous movement of the water.

If the biblical record concerning the geography of Yam Suph is valid, then the miraculous circumstances of its crossing must be carefully considered, even if they cannot be fully explained with scientific tools.

References

Ben-Avraham, Zvi. 1985. Structural framework of the Gulf of Elat (Aqaba), northern Red Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research 90:703-726.

Ben-Avraham, Zvi, and Richard P. Herzen. 1987. Heat flow and continental breakup: The Gulf of Elat (Aqaba). Journal of Geophysical Research 92(B2):1407-1416.

Brenton, Sir Lancelot C.L. 1997. The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English. USA: Hendrickson Publishers.

Brown, Raymond E., et al. 1968. The Jerome Biblical Commentary. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Cassuto, U. 1997. A Commentary on the Book of Exodus. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press.

Fritz, Glen A. 2006. The Lost Sea of the Exodus. USA: Instantpublisher.com.

Fritz, Glen A. 2016. The Lost Sea of the Exodus, second edition. San Antonio: GeoTech.

Gesenius. 1979. Gesenius’ Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon, trans. Samuel Prideaux Tregelles. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House.

Hall, John K. 2000. Bathymetric Map of the Gulf of Elat/Aqaba. Geological Survey of Israel.

Har-El, Menashe. 1983. The Sinai Journeys. San Diego: Ridgefield Publishing Company.

Hellstrom, B. 1950. The Israelites’ Crossing of the Red Sea. Stockholm: Royal Institute of Hydraulics.

Humphreys, Colin 2003. The Miracles of Exodus. San Francisco: Harper.

Josephus, Flavius. 1960. Josephus Complete Works, trans. William Whiston. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel.

Nof, Doron, and Nathan Paldor. 1992. Are There Oceanographic Explanations for the Israelites’ Crossing of the Red Sea? Bulletin American Meteorological Society 73(3): 305-314.

Nof, Doron, and Nathan Paldor. 1994. Statistics of Wind over the Red Sea with Application to the Exodus Question. Journal of Applied Meteorology 33(8): 1017-1025.

Peet, T. Eric. 1923. Egypt and the Old Testament. Boston: Small, Maynard and Company.

Sneh, Y., and M. Klein. 1984. Holocene Sea Level Changes at the Coast of Dor, Southeast Mediterranean. Science, New Series 226(4676): 831-832.

Strong, James. 1990. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

End Notes

[1] Exod. 15:4, 22; Deut. 11:4; Josh. 2:10, 4:23, 24:6; Judg. 11:16; Neh. 9:9; Ps. 106:7, 9, 22; 136:13, 15

[2] rooted in the Hebrew verb amaq

[3] Heap comes from the Hebrew ned (Strong 1990, #5067)

[4] Passover and the start of the Exodus coincided with a full moon. A sea crossing 15-20 days later would have occurred just after the new moon, meaning that no moonlight was available for the Egyptians. Thus, they would have had to wait until first light to determine that the Israelites had decamped and to begin their pursuit.

[5] Among the Egyptian sites proposed for Yam Suph are Lake Menzaleh, Lake Sirbonis, Lake Ballah, the Bitter Lakes, the northern shore of the Gulf of Suez, and a supposed inland sea covering the southern Isthmus of Suez in antiquity (see Fritz 2006).

[6] During the Exodus, Edom occupied the southern mountains of modern western Jordan, just northeast of the modern Gulf of Aqaba. The biblical Mt. Seir was located within Edom.

[7] The southern limit of the land of Canaan had a curvilinear bound extending between the foot of the Dead Sea and the Mediterranean Sea (see Num. 34:1-12).

[8] b’ruakh, written בְּר וּחַ

[9] Strong 1990, #7307

[10] “by,” meaning “to designate either nearness and vicinity…or motion to a place so as to be near it” (Gesenius 1979, 97B).

[11] Yalak (Strong 1990, #3212) is the root form. Yolek is the Hiphil parsing, the imperfect tense, indicating a single process preliminary to its completion.

[12] Whirlwind is translated from the Hebrew gilgal, referring to circular winds (Gesenius 1979, #1534).